Triple Murder in D.C.: Ziang Sung Wan & the Unsolved Mystery that Shocked the Nation

THE CRIME

As far as Chinese immigrants go, Dr. Theodore Ting Wong, Chang Hsi Hsie, and Ben Sen Wu were doing alright for themselves. In fact, it’s safe to say that the three men were likely a source of envy for many in Washington’s Chinese community. Though they dined and shopped in Chinatown, they inhabited the stately Chinese Educational Mission house in the ritzy neighborhood of Kalorama.[1] All three were well educated, hailed from affluent Chinese families, spoke nearly fluent English, and served as diplomats for the Chinese Legation.[1] Ushering in the Chinese New Year on the evening of January 29, 1919, the three men had much to celebrate and even more work to get to the next day. But by morning, the mission house was eerily quiet. The postman rang the doorbell in vain; the milk delivery was left sweating on the stoop; the laundry package sat unattended by the door. Concerned, Kang Li, a neighbor and former tenant of the mission house, entered the house through an open window.[2] What he found sparked a case that would headline papers for years, reach the Supreme Court, and even pave the way for our “right to remain silent.” It was January 31, 1919, and the three residents of the mission had been dead two days.

It was D.C.’s first triple murder involving diplomats, and it was as gruesome a sight as it was unexpected: furniture overturned, bulbs shattered, hardwood stained crimson, and three corpses, all with gunshot wounds. Chinatowns across the U.S. were no stranger to violence; but Kalorama was no Chinatown. Though news outlets related the crime to violence perpetrated by Chinese Tongs, or gangs,[3] the victims were too high profile to run with that crowd. Even more head scratching, the murder weapon found at the scene, a .32 caliber revolver, belonged to Wu, who himself was a victim.[2] The police found no physical evidence to point to a potential suspect. Major Raymond W. Pullman, chief of the Washington police department, had himself quite a case. The intensity of the mystery only fueled his desire to solve it.[4]

THE INVESTIGATION

Kang Li was at first a natural suspect, but as Pullman questioned Li, a more promising suspect came to light.[4] As Li explained, Wong, Hsie, and Wu weren’t the only residents of the mission house.[4] The three men had been hosting a guest, a young Chinese student who stayed at the mission house for a few days and happened to leave the area just before the murder.

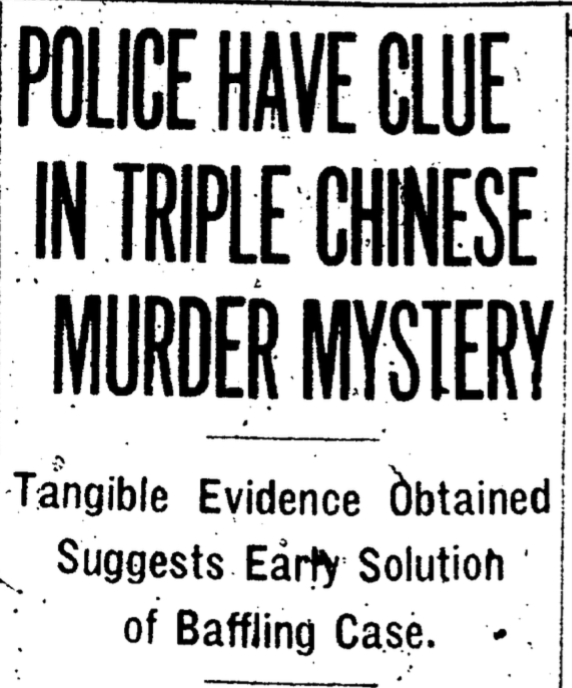

The student’s name was Ziang Sung Wan. It was Li’s understanding that Wan had a friendship with Wu and that Wan’s mother trusted Dr. Wong to look after her son in the States. Li recalled that on that fateful Wednesday, Wan had answered the mission house door. Li had inquired about the whereabouts of Wu and Wong, and Wan had responded that they’d gone out.[5] This was true, as Wu, Wong, and Hsie were out celebrating the New Year; but Li was still “much puzzled by [Wan’s] conduct.”[3]The next morning, Detective Burlingame, one of the force’s best, along with Kang Li, were at Wan’s door in New York City.

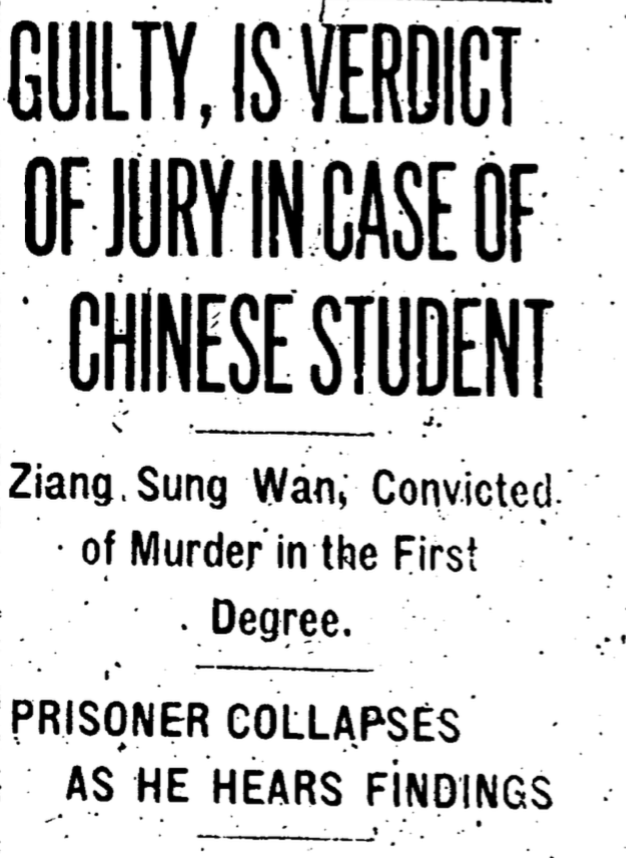

They found Wan with his younger brother, Van. Wan initially refused to come down to Washington for questioning. Though eager to cooperate, he was recovering from Spanish flu and also suffered a severe upset stomach; he didn’t believe such a trip would be good for him. At Li’s urging, though, Wan consented.[3] Wan likely thought he would return to New York in a week; he had no way of knowing he wouldn’t see his home again for seven years.

As The Evening Star would later report, in the time it took for Wan to make his way to D.C., the police had gained a crucial “Clue in [the] Triple China Mystery.”[6] On the day following the murders, an unknown Chinese man attempted to cash a $5,000 check at Riggs Bank.[6] The check, made payable to the bearer, was drawn from the account of the Chinese Educational Mission and bore the signatures of both Wong and Hsie.[7] The teller denied the check out of suspicion. When the news of the murders broke, he was sure the encounter held a connection. Only, the bank teller didn’t recognize Wan. The mysterious man had been “shorter and younger.”[8] Not ready to give up, Detective Burlingame sent for Wan’s brother, Van.

His hunch paid off. The Riggs Bank officers all identified Van as the man in question; and though Van denied all accusations, the police were certain of his involvement.[9] By Friday, February 7, 1919, The Evening Star published that:

"The police no longer look upon the triple murder as a mystery. It is now only a matter of obtaining sufficient evidence of a substantial and convincing nature, the police contend. It has been settled as a surety that the motive was robbery."[10]

THE INTERROGATION

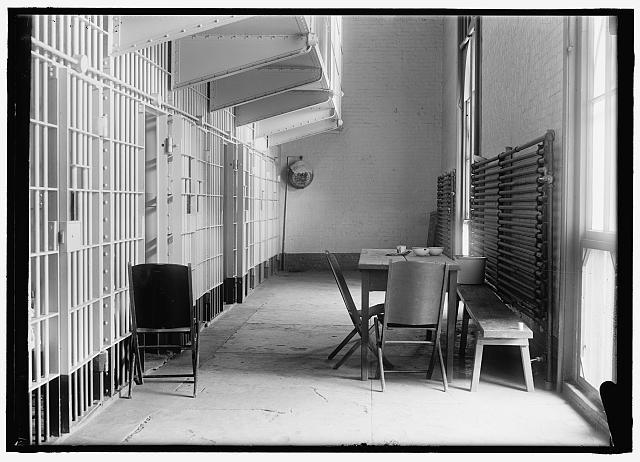

The police lodged both Van and Wan in the Dewey Hotel but kept them on separate floors; neither man was aware of the other’s presence.[11] Seems like a cushy accommodation considering the circumstances, but the truth of it depends on who you ask.

According to Van, the police made it clear Van wouldn’t be allowed to eat, sleep, or see his brother unless he confessed to the murders.[12] During questioning, police “cursed, pinched, and shoved” Van repeatedly.[12] “They must get somebody,” Van remembered them saying, as the Chinese Legation was putting pressure on the investigation.[12] Wan and Van both recall police usage of profanity and being called names like “yellow rat, ‘Chink,’ and skunk.”[13] Detectives interrogated Wan for hours on end, even in spite of his sickness, fatigue, and requests for breaks.[13] “Sometimes we did and sometimes we did not let him alone,” one of the detectives recalled.[13]

There’s no question Wan suffered immensely from his physical ailments. He experienced symptoms of Spanish flu, which he had previously contracted, as well as constant abdominal pain and constipation. He couldn’t eat and spent most of his time bedridden; but the questioning didn’t stop. Even newspapers became aware of Wan’s illness: “Physicians Find Chinese Slayer Is In a Precarious State of Health,” reported The Evening Star.[14]“Physician said his mental worry is not calculated to have a beneficial effect on his physical condition.”

The detectives, though, recalled that though Wan was subject to questioning, he also was treated to complementary meals and cigars.[13] Maj. Pullman even remembered that he and Wan would discuss matters such as “international politics, the League of Nations, and Chinese customs and literature” to put a pause on the interrogation.[13] Even so, there’s no doubt that given Wan’s physical condition, the interrogation was intense.

By Saturday, February 8, the police were getting impatient. Neither Wan nor Van were talking. Perhaps the police had been playing too nice. That evening, detectives brought the brothers to the scene of the crime, hoping to amp up the pressure.

For hours, the police walked Wan through the mission house, pointing out the blood stains and showing Wan photos of the corpses. Using “lighting and other methods,” the police attempted to re-enact the crime, even going so far as to place the murder weapon in Wan’s hands.[15] In Wan and Van’s memory, it was a brutal night. The detectives refused them water, food, and the bathroom.[16] Both Van and Wan were referred to repeatedly as “yellow rats” or “skunks.”[16]

“He is as cold-blooded a Chinaman as I ever saw,” Maj. Pullman reportedly said of Wan. “Why don’t you admit and let your brother go? You say you are a good Christian and love your brother. Why don’t you admit?”[16]

“We won’t let you alone until you admit how you killed them,” Van remembers detectives saying.[16] “Don’t think you are home. You are in our power. You have got to do what we say.”[16] After being shown Dr. Wong’s checkbook and samples of his own writing, Wan finally confessed that he forged the writing on the stub.[17] Though exhausted and in excruciating pain, he refused to admit to more. It was 5 am by the time the brothers were permitted to leave.

But their stay at the hotel was over. Wan’s confession to forgery and Van to being his accomplice meant Maj. Pullman could place them formally under arrest. The police brought the brothers to the Tenth Precinct Station House, where they narrowed in on Wan’s weakness.[18] “If you are guilty and your brother is innocent, now is the time to tell it,” implored Inspector Grant. “I am holding your brother just the same as I am holding you.”[19]

Perhaps fatigued from the relentless pressure, Wan decided he was ready to talk. At first, Wan admitted to being at the house at the time of the crime but denied any participation. But there was a lot of Wan’s story that simply didn’t add up. After further interrogation, Wan eventually broke.

“Yes, I will tell you the whole truth now.”[19] Wan and Wu had conspired together to steal from the mission, Wan explained. The night of murder, Hsie caught the two men with the checkbook in the kitchen. Wu took out his revolver and shot Hsie in the back. Wu returned to the kitchen and continued to discuss matters about cashing the check. It wasn’t long, though, before Wong entered the house. As soon as Wong entered the kitchen, Wu pointed his pistol and shot him point blank.[20] Wu then instructed Wan that both of them were responsible for killing Wong and Hsie. Wan at first protested, but he then formed another plan of action. He resolved, he told the police, to kill Wu. Discreetly picking up Wu’s pistol, Wan suggested they load more coal in the furnace. Once in the furnace room, Wan shot Wu.[20]

Wan insisted that his brother knew nothing of the murders, and that he merely used Van as a tool for cashing the check.

“I’m glad this is off my mind,” Wan reportedly told Inspector Grant. “Dr. Wong was my friend, and my mother in Shanghai had entrusted him to care for me in this country. I never wanted him killed, so I killed Wu for what he had done. I am glad it is all over. You now have the whole truth. I am not going to fight the case you have built against me. I want no lawyer. I know what I have done, and I will ‘take my medicine,’ as you Americans say.”[21]

Wan’s viewpoint changed, though, when the coroner’s jury found both brothers responsible for all three deaths. “I must have a lawyer now, because they do not believe what I tell them. I have told them the truth that my brother might not suffer. Now they are going to punish him, too. I must make them understand that I am the only man living who is to blame.”[22]

With the help of friends, Wan was able to afford legal counsel, and he repudiated his confession.[23] As Wan would later tell the jury, he signed the police’s typed confession in the jail’s Red Cross room after being diagnosed with colitis; the police had cornered him in a moment of weakness and excruciating pain.[24]

Even United States Attorney John E. Laskey, who “took intense interest in the case”[23] and later led the prosecution, believed the police should have approached the interrogation differently. Due to the faulty circumstances of Wan’s confession and police oversights in the investigation, Laskey had to delay indictments until end of September.[25] The grand jury handed down four indictments,[26] but both brothers pleaded not guilty before Judge Ashley M. Gould.[27] Van was fixed a bail of $3,000. Wan’s fate, though, ultimately rested upon trial.

THE TRIAL

The prosecution told a story of man in desperate need of money, honing in on the true point that Wan faced financial difficulties.[28] Although Wan’s wealthy mother supported him and his brother, Wan held major debts due to a failed business venture.[29] The defense case painted Wan as an innocent but ill man who had simply been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Being unaware of his rights and of the American criminal justice system, Wan was an easy scapegoat for the police.

It seemed neck in neck, but the tide turned when the judge ruled Wan’s signed confession admissible. The defense protested, as the Supreme Court ruled in the 1897 case, Bram vs. United States, that a confession coerced by third degree methods[30] was not to be admitted.[31] Although Bram established that a variety of police behaviors could compromise a confession, the SCOTUS ruling still allowed for a lot of grey area, and testimony of Wan’s good treatment at the hotel made the severity of Wan’s illness difficult to prove. It was a massive blow to the defense. On Friday, January 9, 1920, the jury found Wan guilty of murder in the first degree. The penalty of the verdict was death. As the court read the verdict, Wan collapsed and burst into sobs.[32]

THE AFTERMATH

This in and of itself is quite a story, but the significance of Wan’s case actually lies in the aftermath. Over the next seven years, Wan’s lawyers fought to delay his penalty and appeal his case, and the appeal eventually made its way to the Supreme Court in spring 1924.[33]

The matter in question was whether Wan’s confession should have been admissible. Though the court had previously ruled on third degree in Bram vs. United States, the decision seemed to need some clarification.[34] Wan got lucky in that by 1924, public criticism of “third degree” methods had reached an all- time high.[35] It seemed like both the nation and the Supreme Court justices were willing to empathize.

On October 13, 1924, seven years after Wan’s initial arrest, Justice Louis Brandeis read the decision of Ziang Sung Wan vs. United States.[36] “The undisputed facts showed that compulsion was applied…The alleged oral statements and the written confession should have been excluded.”[37] It was a landmark decision for both Wan and the country, and it set an important precedent.

Forty-two years later, in 1966, Chief Justice Earl Warren remembered Wan v. United States when writing his opinion for Miranda v. Arizona, the famous case that established one’s Miranda rights, or “right to remain silent.”[38] Warren quoted liberally from Wan’s case, arguing that in the same way certain police behavior should be outlawed, certain police behavior should also be ensured.

Wan hadn’t anticipated nor asked, though, for such a historic story. Like most immigrants, he came to the U.S. in expectation of a better life. It’s safe to say that America wasn’t as promising as he’d hoped. Wan returned to China a few years after gaining his freedom. As far as the true culprit of the triple murder, that’s still a mystery…

AUTHOR'S NOTE

For more on Wan's story, check out Scott D. Seligman's book, The Third Degree (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018), which was a leading source for this article.

Footnotes

- a, b William E. Peake, “Cryptic Crimes and Chinatown: The Story of the Wily Oriental's ...” The Washington Post (1923-1954); Jul 21, 1929; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. SM6

- a, b Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 21.

- a, b, c “POLICE HAVE NO CLUE IN TRIPLE CHINESE MURDER MYSTERY,” February 3, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1

- a, b, c Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 24.

- ^ United States v. Ziang Sung Wan, Testimony of Kang Li, Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, September 30, 1919

- a, b "REGISTER IN HOTEL MURDER EVIDENCE," February 5, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 2

- ^ “CLASH IN WAN TRIAL: WITNESS LI'S STORY DISAGREES WITH THAT OF LETTER ...” The Washington Post (1877-1922); Dec 17, 1919; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 1

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 35

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 37

- ^ CHINESE MURDER MYSTERY CLEARS,” February 7, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1.

- ^ “WAN AND BROTHER GUARDED IN HOTEL,” February 8, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1.

- a, b, c Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 36

- a, b, c, d, e Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 41

- ^ “WAN ILL, DESPONDENT, MAY DIE IN SIX MONTHS,” February 15, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 2

- ^ POLICE REHEARSE CHINESE MURDERS IN MISSION HOUSE,” February 9, 1919, Evening Star (published as The Sunday Star.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1.

- a, b, c, d, e Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 47

- ^ United States v. Ziang Sung Wan, Testimony of Edward J. Kelly, Raymond W. Pullman, and Clifford L. Grant, Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, September 30, 1919

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 49

- a, b United States vs. Ziang Sung Wan, Testimony of Clifford L. Grant, Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, September 30, 1919

- a, b “Wan Confession In,” The Washington Post (1877-1922); Dec 19, 1919; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 1

- ^ “Wan Confesses Killing of Wu, Who Slew Two,” Washington Times, February 11, 1919.

- ^ “Insists Van Had Nothing to Do With the Killing,” Washington Times, February 12, 1919.

- a, b “WAN MAKES FOR LEGAL BATTLE,” February 23, 1919, Evening Star (published as The Sunday Star.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 14.

- ^ “Sung Wan, Chinese Held as Slayer, Ill,” Washington Post, February 13, 1919

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 58-59

- ^ “HOLDS WAN ALONE SLEW CHINESE TRIO,” September 30, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1.

- ^ “ZIANG SUNG WAN PLEADS NOT GUILTY OF MURDER,” October 8, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 3

- ^ “ASSERTS WAN SLEW TO RECOUP LOSSES,” December 15, 1919, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 2.

- ^ “WAN TAKES STAND; TELLS LIFE STORY; TRIAL NEAR CLOSE: DECLARES ONE OF ... “The Washington Post (1923-1954); Feb 5, 1926; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 2

- ^ Meaning one where law enforcement made promises, threats, or other acts to induce said confession.

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008, p. 87

- ^ “GUILTY, IS VERDICT OF JURY IN CASE OF CHINESE STUDENT,” January 9, 1920. Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 1

- ^ “SUPREME COURT HEARS APPEAL FOR SLAYER,” April 8, 1924, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 38.

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 87

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, The Third Degree, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008), p. 101

- ^ “Ziang Sung Wan vs. United States,” Cornell Law School: Legal Information Institute, https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/266/1, Accessed 13 April 2020.

- ^ Scott D. Seligman, “The Triple Homicide in D.C. That Laid the Groundwork for Americans’ Right to Remain Silent,” Smithsonian Magazine, 30 April 2018.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)