When Arlington Set the Nation's Clocks: The Arlington Radio Towers

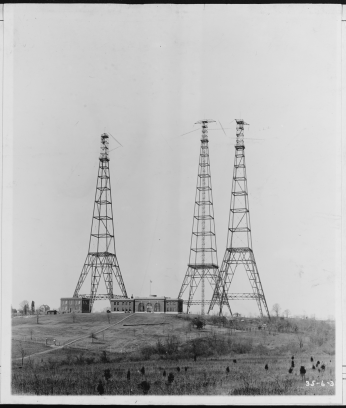

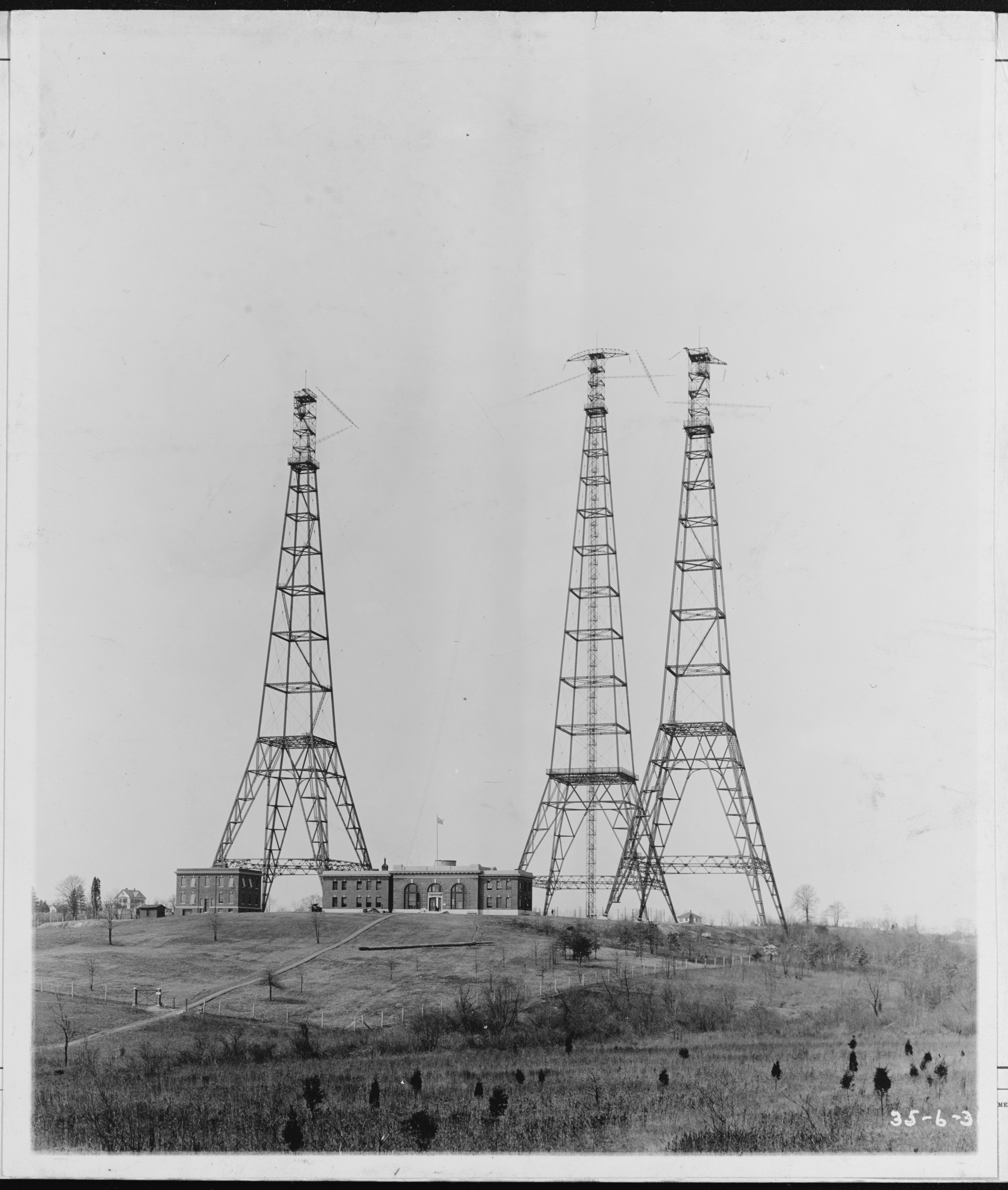

If you were tasked with locating the tallest structure within the skyline of Washington, D.C., you’d be right to point at the Washington Monument. But from 1912 to 1941, just across the Potomac River and into Virginia, there was another manmade structure that was even taller than the beloved stone obelisk and was a treasured sight for residents of Arlington County.[1]

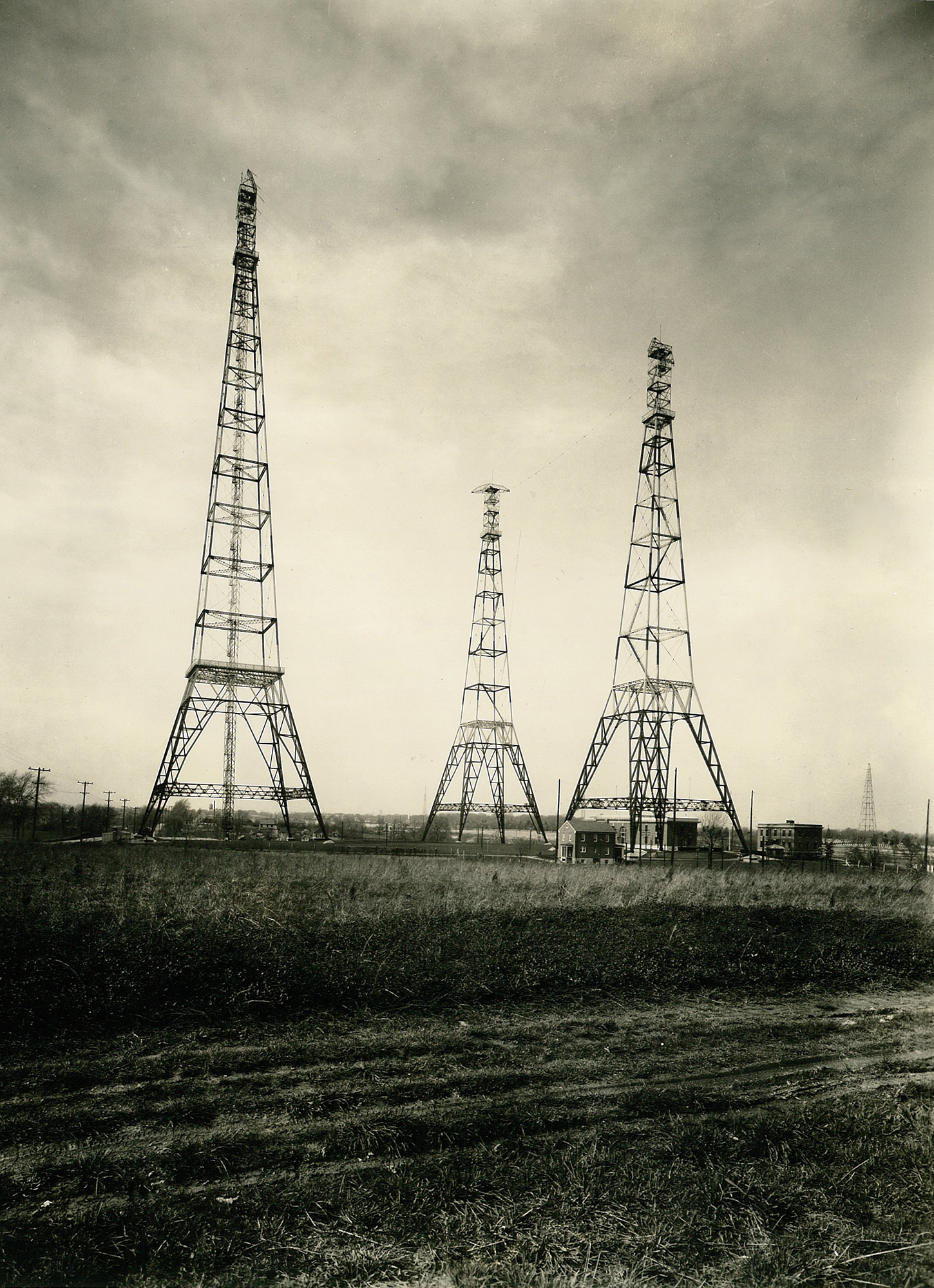

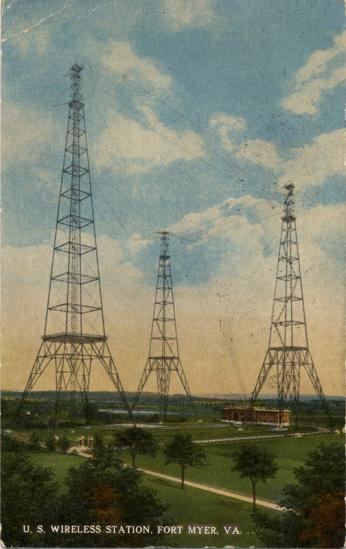

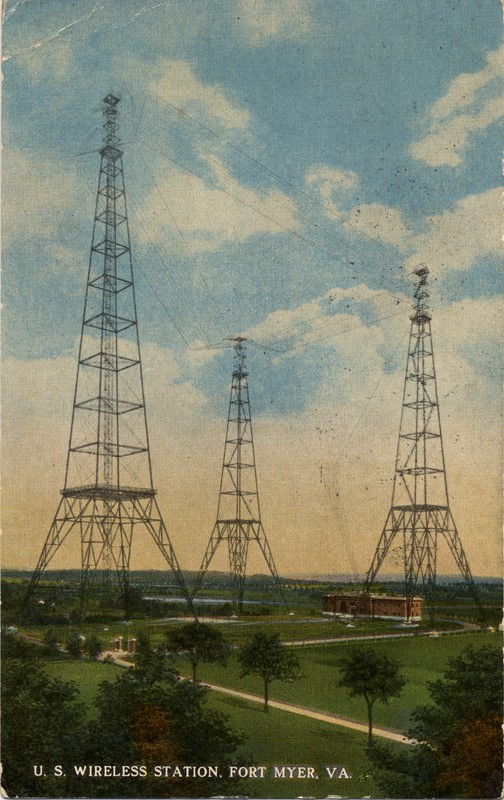

Just off the intersection of Columbia Pike and Courthouse Road, a collection of radio transmission towers dominated Washington’s skyline for more than a quarter of a century. The tallest among them—taller than the Washington Monument (555ft)—stood at 600 feet! It was also once the second tallest radio tower in the world next to the 630 feet tower at the German naval station in the town of Nauen, Brandenburg.

But the towers were more than just a visual sight to behold. Between 1913 and 1936, they set the clocks for the entire nation with their daily time signals.[2] They were also responsible for making the word “radio” an industry standard.[3] But most importantly, Arlington was considered the “most powerful wireless telegraph station in the world,”[4] and its pioneering advancements and experiments in communications technology helped usher in an era of wireless communications across the globe.

The towers were attached to the Arlington Radio Station of the United States Navy, also known by its call letters, “NAA.” The station was constructed as part of a project to build an empire-wide, long-distance wireless radio communications network—at the time called “high-power radio telegraphy.”[5] These powerful radio stations would link America’s fleet at sea while providing fast and reliable communication between the ships and Washington.

The project called for seven radio stations around the globe:

• San Francisco

• Colón (the Atlantic terminal of the Panama Canal)

• The Hawaiian Islands

• Samoa

• Guam

• The Philippines

• And… Arlington, Virginia

The expectation was that with the completion of all seven stations, “the navy and Washington will be accessible to each other from every corner of the world.”[6] Together, the electrical waves of all seven stations were estimated to cover about 198,390,800 square miles of continent and ocean.[7]

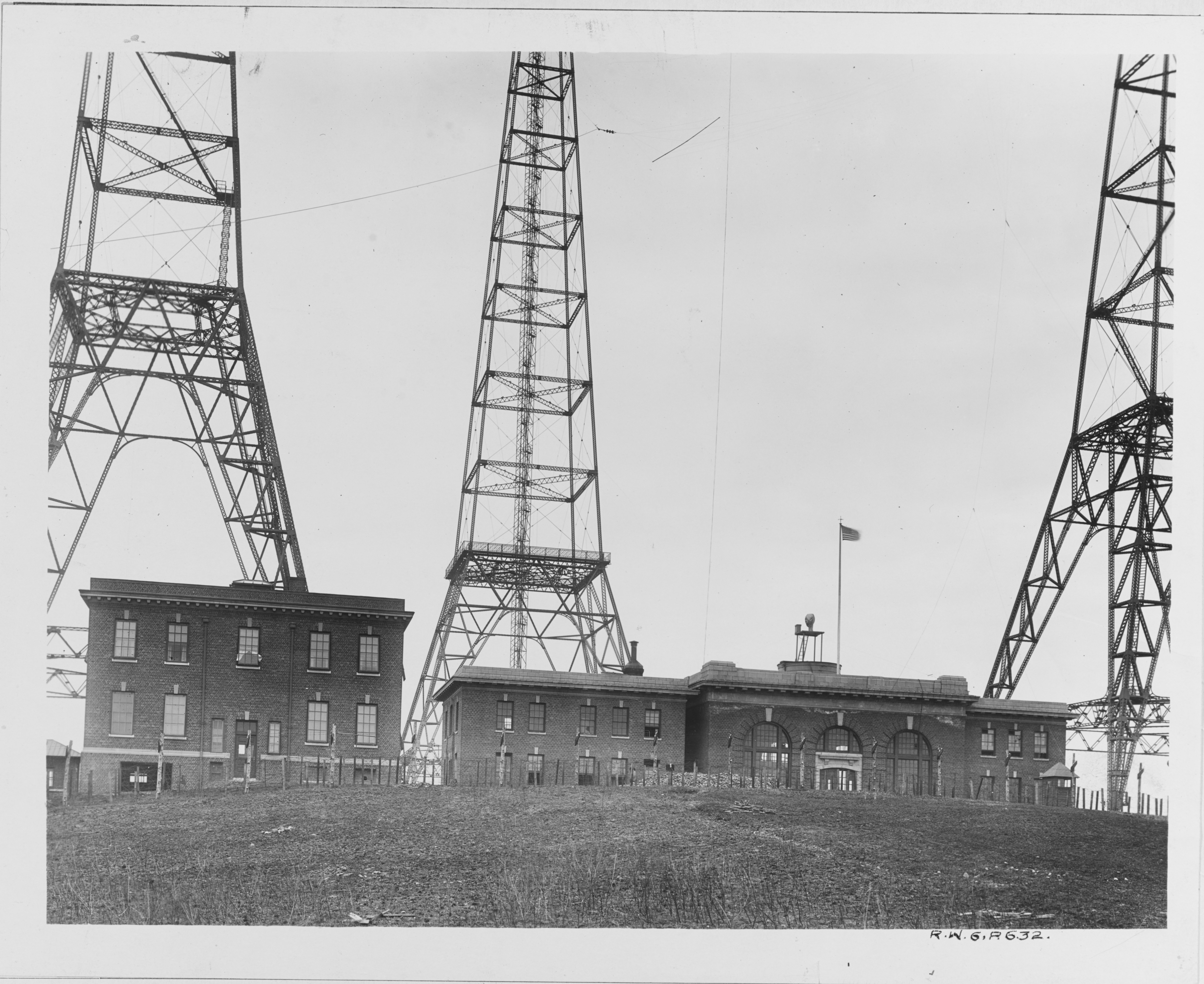

In 1911, a patch of land adjacent to Fort Myer in the Arlington Heights community was chosen for the construction of the first of seven radio stations.[8] The radio towers were modeled off the Eiffel Tower and were constructed by the Baltimore Bridge Company. The first tower, standing at 600 feet, consisted of four legs that were each 150 feet apart and 150 feet high. It was joined by two other towers, each standing at 450 feet with legs 125 feet apart and 150 feet high. Telegraph cables wrapped around the antennae at the peaks of each tower, linking the three behemoths together. The cable then drooped down to the receiving and sending rooms in the central building located at ground level.

Within the central building were the station’s electrical plant and operating rooms, housed at both ends of the building. In the transmitter room was a 100-kilowatt generator, which helped the station reach a communications range of 3,000 miles. However, under “freak weather” conditions, the station was estimated to be able to reach at least four or five thousand miles—and potentially as far as Japan![9] In comparison, the “best naval radio stations on shore” at the time had only a 35-kilowatt capacity, and most naval vessels had only a 10-kilowatt capacity.[10]

The walls of the operating rooms were padded with felt to absorb the vibration caused by the machinery and avoid any technical complications. One room was occupied by radio operators while the other by those who manned the land wires, which sent out radio messages by telephone or land wire via the Western Union and Postal Telegraph companies (with whom the station would share its radio services) or by the Navy’s private communications line (to prevent any eavesdropping into military messages). And for the radio operators, “absolute silence” was provided by means of thick, sound-proof walls to prevent any disturbances to their work.

The towers were completed in September 1912, and in October the station ran its first test transmissions at little more than half power.[11] In its inaugural act, the Arlington Station was able to get Clifden, Ireland, over 2,500 miles away, into communication.[12] Days later, a wave of test transmissions was sent to stations across the world and to U.S Navy ships.[13] Upon receiving a transmission from Arlington, a station would typically send a message back. The Washington Post reported one such reply when the station in Colón responded back to Arlington by radio, “Got you fine.”[14]

Just before the year closed, Arlington made another achievement that heralded further success for the new year. At five minutes before midnight on December 31, Arlington sent out its first-ever time signal that reached navigators in every part of the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, the West Coast, and Paris.[15] And earlier that afternoon, Arlington received its first midnight time signal from the Eiffel Tower station in Paris (which is 6-hours ahead in time from Arlington), confirming the potential of NAA to reach nearly 4,000 miles in distance.[16]

Other than radio communications, Arlington was to send out daily time signals, weather forecasts, hydrographic bulletins (measurements and descriptions of bodies of water), and other information useful to navigators at sea.

The press frequently reported on additional wireless communication links made between Arlington and other radio stations and ships, reflecting the excitement with which the novel radio technology was received by many in America. A noteworthy example is a Baltimore Sun report from November 1913, which noted that after weeks of “patient experimentation,” Arlington was able to hear the ticking of the Paris Observatory clock as transmitted by the Eiffel Tower.[17]

In September 1915, Arlington made yet another exciting achievement with its first wireless transmission of a human voice to the radio station in Pearl Harbor, a distance of 4,600 miles—far greater than that from New York to London, Paris, Rome, or even Berlin.[18] Just eleven years prior, the renowned inventor Nikola Tesla predicted that a human voice would soon be heard at such a distance. Now, that prediction became a reality.[19] “These tests made between Washington and Honolulu will act as an immense stimulus to wireless telephony,” Tesla said.[20]

A few weeks later, and under tremendous difficulty due to France’s wartime conditions, “Hellos” and “Good-byes” were permitted to be received—and were successfully heard—by the Eiffel Tower station from Arlington.[21] But the increasing necessity for uninterrupted military communications in France soon put a halt to all experiments between Arlington and Paris.[22] Following this announcement, the Washington Post headline read: “Mustn’t Phone to France.”

But as the pressure of the Great War on the European continent pounded harder on America’s front door, Arlington Radio Station was about to perform another historical action…

Upon President Woodrow Wilson’s request for a declaration of war against Germany, shock waves were felt across the world. And after Congress approved his request, radio waves soon followed. As the president signed the war resolution on April 6, 1917, it was Arlington that heralded the modern declaration of war through its radio broadcast, announcing to the entire world that America had entered the fight.

But whereas today the ubiquity of wireless and radio transmissions leaves us practically blind to the convenience of near-instantaneous (and mostly invisible) communication, such wireless immediacy inspired an astonishing paean from one writer who was still acclimating to the novelty of wireless radio technology. As Arlington announced America’s entry into the Great War, a writer in the New York Times described the technology behind the radio broadcast as a “new magic, as mysterious, after all explanations, as the fabled arts by which Thessalian witches drew down the moon or Malay soul-catchers capture the souls of sleeping enemies.”[23] The closest metaphors at hand to describe the processes behind such a monumental broadcast could only be found in the otherworldly:

“Man conjures potent spirits with his brain, projects his word over the globe, makes the air his messenger, out of forces which he still imperfectly comprehends. …The wireless and electricity speak the primeval word ‘war.’”[24]

Alongside its advances in communications technology, the Arlington towers also developed quite the reputation among local residents. The station quickly picked up a nickname based on its behemoth towers, “The Three Sisters” (not to be confused with the Three Sisters Islands cluster in the Potomac River and the controversial Three Sisters Bridge construction project named after the islands). And overtime, the station became a beloved sight for local residents, whose city was becoming a key hub in advancements in radio communications technology (which was somewhat ironic, given that the original plans to build the towers were met with objections due to its potential to overshadow the Washington Monument).[25]

In fact, local residents were so enamored by the towers that after a snowstorm in 1920 caused significant outer damage to the towers, “mariners, jewelers, farmers, amateurs and others, by radio, by telegram, by letter, and in sundry other ways, transmitted a long wail to the Navy: ‘What in the world has become of our old friend, NAA?’”[26] Ironically, the towers were still operational for at least two days after the damage was done. It was merely the extent of the appearance of damage that so stunned area residents.[27]

Local love for the towers soon translated into the creation of postcards and other memorabilia. Even the local neighborhood, streetcar stop, and post office were renamed “Radio” in honor of the Three Sisters.[28] By 1923, two additional 200ft towers were constructed (though the towers never came to be referred to as The Five Sisters).[29]

For many years later, Arlington continued to make numerous advancements in military and radio communications technology. But unknown at the time of its construction, the fate of the Arlington radio towers was sealed by another piece of technology that preceded it by an entire decade: the airplane.

By 1933, the nearby Washington-Hoover Airport was rated by pilots to be the most dangerous airport in America.[30] As one might expect from having three massive radio towers close by, Arlington Station was deemed a significant hazard to aircraft. It wasn’t helped by the fact that the towers were also painted in a “landscape-blending gray, black, and yellow” that only added to the anxiety of pilots (they were later painted orange and white in 1936 as an air safety measure).[31] In fact, the possibility of a major disaster occurring at the airport plagued the mind of President Franklin Roosevelt—who once had a nightmare of a horrific plane crash occurring at the site.[32]

So, in 1938, FDR ordered the Civil Aeronautics Authority to make plans for a new airport, which entailed the dismantlement of the towers. As construction on the new Washington National Airport was set to wrap by the middle of 1941, the Navy kept its promise by dismantling the Arlington radio towers. All future radio transmission would be carried out by the station in Annapolis, Maryland. By this point, Annapolis had already taken over much of the broadcasting operations from Arlington over the years, so the move wasn’t a difficult decision to make.[33] In fact, as the Washington Evening Star put it, Arlington was “no longer of any real value to the Navy in communicating with the fleets at sea or relaying weather reports to mariners since the introduction of the short-wave radio.”[34] In truth, in its final years, NAA was simply not as talkative as it was in its infancy.[35] And just before the new airport opened in June that year, the towers were gone.

The station itself remained in operation until 1956, where it “served primarily as a link between the different Naval Communication Stations in Washington, D.C."[36] But in July of that year, the station finally shut down, “followed by various ceremonies championing the legacy of the bygone structures and the station,” according to Arlington Public Libraries.[37]

Today, nothing remains of the radio station other than a historical marker and a nearby sculpture entitled “Echo” by Richard Deutsch, inspired by the Three Sisters and Arlington’s contribution to communications technology.[38]

Yet the loss of the towers still left a tragic impact on Arlington residents, who lost not only a visual artifact and reminder of their city’s role in advancing communications technology, but a behemoth sight that defined the area for over a quarter of a century. One writer eulogized in the pages of the Northern Virginia Sun: “The skyline will seem blank to those accustomed to the sight of the ‘three sisters,’ but, like everything else, the sense of their loss will not last long. Time moves too fast for that.”[39]

Footnotes

- ^ “Baltimore-Built Towers For Greatest Wireless,” Baltimore Sun, November 10, 1912.

- ^ “What Happened to Arlington’s Radio Towers?,” Arlington Public Library, December 19, 2019, https://library.arlingtonva.us/2019/12/19/what-happened-to-the-arlington-radio-towers/.

- ^ Matt Blitz, “A Tale of Three Towers,” Arlington Magazine, October 2, 2017.

- ^ “Baltimore-Built Towers."

- ^ “Army and Navy Gossip,” Washington Post, October 6, 1912.

- ^ “Baltimore-Built Towers."

- ^ “Navy Has World’s Most Powerful Wireless Station,” New York Times, October 20, 1912.

- ^ “What Happened to Arlington’s Radio Towers?.”

- ^ “Navy Has World’s Most Powerful Wireless Station."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.; “Hear Arlington at Colon,” Washington Post, November 10, 1912.

- ^ “Baltimore-Built Towers."

- ^ “Gets Message 2,800 Miles,” Washington Post, October 31, 1912; “Hear Arlington at Colon”; “Long Wireless Messages,” Washington Post, November 15, 1912.

- ^ “Hear Arlington at Colon."

- ^ “Time Signal By Wireless,” Washington Post, December 25, 1912; “Wireless to Greet 1913,” New York Times, December 25, 1912; “News of the Shipping,” Baltimore Sun, December 30, 1912; “Point Loma Receives Time Signal,” Washington Post, January 1, 1913; “New Year Wish by Wireless,” Baltimore Sun, January 1, 1913.

- ^ “Paris Signals Arlington,” New York Times, January 1, 1913.

- ^ “Clock Ticks Across Ocean,” Baltimore Sun, November 22, 1913; “Paris Time by Wireless,” New York Times, November 22, 1913; “Sends Times to Paris,” Washington Post, November 23, 1913.

- ^ “Phone Hawaii by Air,” Washington Post, October 1, 1915.

- ^ “Nikola Tesla Sees A Wireless Vision,” New York Times, October 3, 1915.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Vision of Years Achieved,” New York Times, October 22, 1915.

- ^ “Mustn’t Phone to France,” Washington Post, October 31, 1915.

- ^ “A Modern Declaration of War,” New York Times, April 8, 1917.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Navy Has World’s Most Powerful Wireless Station."

- ^ Donald Wilhelm, “NAA,” in Radio Broadcast: Radio For Every Place and Purpose, vol 2, 1922-1933, edited by Arthur H. Lynch (New York: Double Day, 1923).

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Matt Blitz, “A Tale of Three Towers,” Arlington Magazine, October 2, 2017, https://www.arlingtonmagazine.com/tale-three-towers/.

- ^ “Fourth Arlington Radio Tower,” Washington Post, September 12, 1922; “What Happened to Arlington’s Radio Towers?."

- ^ Alastair Gordon, Naked Airport: A Cultural History of the World’s Most Revolutionary Structure (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004), 117.

- ^ Malinche MacEvoy, “Arlington Radio Towers to Be Repainted as Air Safety Measure,” Washington Post, December 6, 1936.

- ^ Gordon, Naked Airport, 117.

- ^ “Navy Asks Bids On Arlington Radio Towers,” Washington Post, January 3, 1941.

- ^ “Arlington Towers Will Go to Highest Bidder Wednesday,” Evening Star, January 5, 1941.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “What Happened to Arlington’s Radio Towers?."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Echo,” Arlington County Virginia, accessed May 11, 2022, https://www.arlingtonva.us/Government/Programs/Public-Art/Public-Art-Collection/Permanent-Collection/Locations/Echo.

- ^ “What Happened to Arlington’s Radio Towers?."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)