Was Lisner Auditorium Really Desegregated in 1947?

The anticipation hung heavy in the air as finely dressed men, and women gingerly followed ushers to their assigned velvet seats inside Lisner Auditorium. Chatter filled the cavernous space, discussing the merits of the evening’s main attraction, the new Maxwell Anderson play, Joan of Larrain.[1] The show’s lovely leading lady, Ingrid Bergman (of Casablanca fame), drew crowds to the newly built George Washington University theater on this fateful opening night, October 29, 1946.[2]

Just a little over one year after the conclusion of the Second World War, the District was still in the process of settling back into a peacetime existence. Instead of spending every waking moment focused on winning the war and merely surviving, Washingtonians were ready to return to a state of thriving. One way arts leaders hoped to do so was by establishing Washington, DC, as a cultural center for the nation where the arts would be supported and flourish.[3] You know, give New York and Los Angeles a rival in attracting culturally significant opportunities, like serious theater. But growing Washington as an arts capital was more complicated than just attracting leading talent to District stages.

On the unseasonably warm October night in question, a number of African American Washingtonians hoped to watch Ingrid Bergman grace the Lisner stage as the historical heroine, Joan of Arc.[4] Due to the hype surrounding the play, tickets went on sale via mail order, effectively allowing any person to purchase a seat.[5] But, when it came time for the curtain to go up, all the white patrons were kindly shown to their seats, while all the African American theatergoers were denied entry.[6]

The episode highlighted one of the intricacies of Jim Crow era life in Washington. While much of the South had enacted legislation to ensure African Americans stayed out of whites-only establishments, Washington, DC had comparatively fewer such laws on the books.[7] Still, segregation was deeply ingrained in D.C. life. Schools and recreation facilities were separated by race and private business owners set their own policies on who was welcome.[8]

When it came to Washington's theaters, this created a lack of uniformity.[9] Constitution Hall allowed people of color to sit in the audience but famously allowed only whites to perform on stage. At the National Theater, the opposite was true. With Joan of Larrain being Lisner’s first big-ticket commercial event, George Washington University had to decide what level of integration they would allow at public, non-university events held in the theater.

The school made a predictable decision. Unlike American or Catholic Universities, which were integrated at the time, GWU did not admit African American students.[10] So, it was little surprise that the University also decided to prohibit African American patrons from entering the theater.

The first test of the new auditorium’s policy came on October 9, just three weeks before the debut of Joan of Larrain.[11] During a performance of “Ballet for Americans,” two black Washingtonians attending the show with other members of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare were denied entry.[12] The Committee chairperson of the group, Dr. Joseph L. Johnson, sent a complaint via telegram to Cloyd H, Marvin, President of the University, regarding the poor treatment by the Lisner staff to his members.[13] In response to the query, President Marvin explained that the university was simply following in the footsteps of other local theaters when they excluded African Americans from their audience.[14]

The following day, October 10, The Evening Star published a short piece on the matter.[15] As word of the incident slowly spread throughout the city, discrimination became a frequent topic of conversation among the city’s residents. October 19 brought with it the news that the production company of Anderson’s and Bergman’s upcoming play— The Playwrights Co.— were unaware of the venue’s segregation policy and were displeased by the revelation.[16] While the producers hoped the university auditorium would permit all paying theater-goers their rightful places in the audience, the group said its hands were tied due to contracts and thus could not exert more pressure.[17]

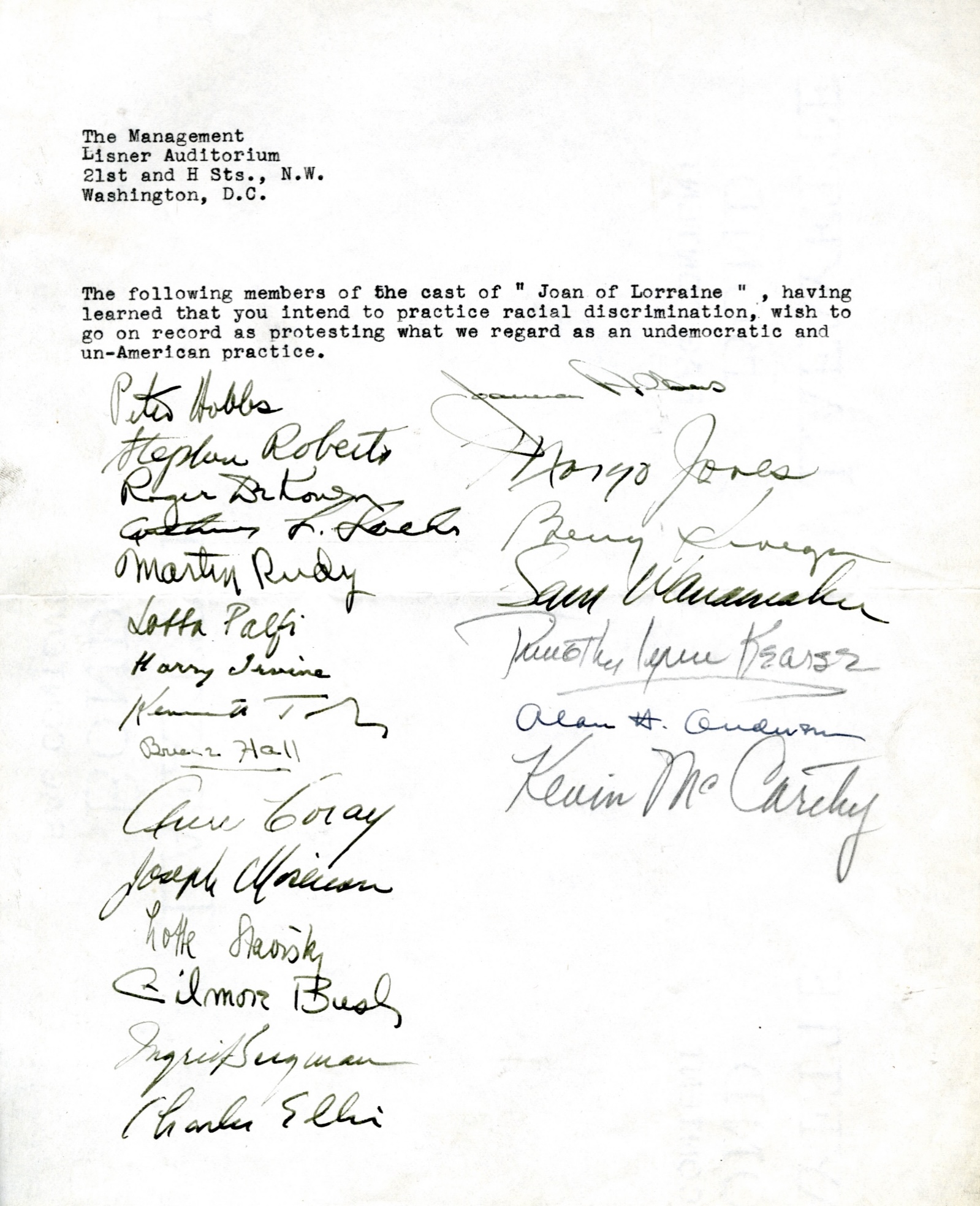

Bergman was particularly disturbed by the events surrounding the show. In a pamphlet, which was handed out in protest, Bergman said “I feel very bad about the policy of discrimination at Lisner Auditorium. I wouldn't have come if I had known in time.”[18] She went on to say that “entertainment is for all the people.”[19]

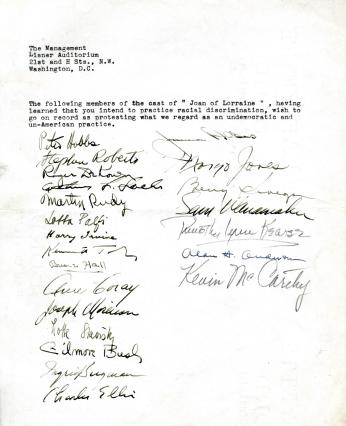

The stance did not sit will with some. As Bergman was leaving her dressing room in Lisner, a segregationist physically and verbally assaulted her, spitting and calling the actress a racist epithet.[20] Infuriated by actions of the university, Bergman along with her fellow cast members signed a petition registering their disapproval of the University's discriminatory policy.[21]

Then, on October 29 — the same day that Joan of Larrain premiered on Lisner’s stage — both The Washington Post and The Evening Star published an editorial by Robert E. Sherwood (a Pulitzer Prize and academy award-winning Screenwriter/Playwright), making all of DC aware of just what was going on at the new theater.[22]

Sherwood rounded out his scathing critique of Lisner — and D.C. as a whole — with a call to action for those in the arts community.

The revenue to be derived is poor compensation for the injury done to the conscience of American citizens by this continuance of injustice in our, National Capital. I believe that only a small minority of the people of Washington want this to continue—and there is surely no law compelling that minority to go to the theater if they object to the presence of Negroes under the same roof. Therefore, I believe that it is the duty of all of us who work in the American theater—actors, playwrights, producers —to protest against this intolerable situation by agreeing that we shall keep our productions out of Washington until the ban against Negroes is abolished.[23]

Even though this editorial made its way into the District’s two major newspapers, GW held firm and refused to honor any tickets bought by African American patrons for that evening’s debut performance.

Reactions by both Washingtonians as well as GW students were swift and immediate. Letters to the editor poured in from all over the DMV.[24] While some stood in solidarity with segregation practices, the vocal majority praised Robert Sherwood and called for change.[25]

One letter, in particular, stood out:

On Thursday afternoon, October 31, a Negro girl sat through the matinee performance of "Joan of Lorraine" in Lisner Hall, the new national shrine of white supremacy. I was that girl. I sat in row M, seat 11. I was admitted not because the managers of the hall suddenly had relented and become Christians or practitioners of democracy, but "only because they failed to recognize me as being one of a proscribed race. My darker brothers, more easily recognized than I, were not admitted, yet I am as much a Negro as they are. I— a Negro—sat in this lily white audience, but— wonder of wonders— the world around me did not crumble.[26]

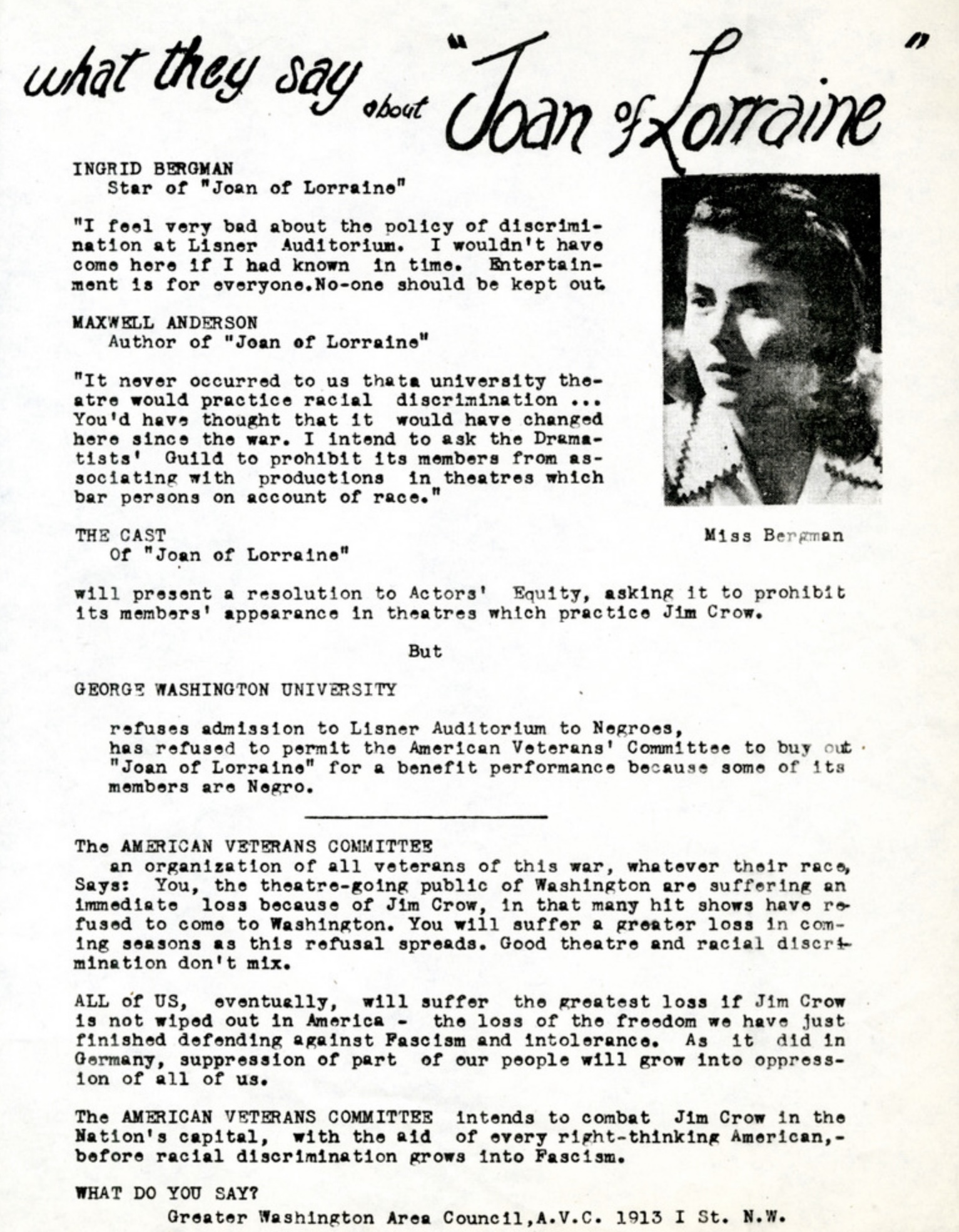

A picket line formed outside the Foggy Bottom theater, protesting the racist actions of President Marvin and GWU as a whole.[27] The primary organizer was chapter 341 of the American Veterans Committee, made up of both GW students as well as white and African American non-students.[28] Although the university refused to acknowledge the AVC as an official school-sanctioned organization due to the group’s political nature, that didn’t stop the administration from threatening to expel student leaders involved with the chapter. Among the reasons given for the threatened punishment was a charge that the students inaccurately asserted that the AVC represented all of some 6,000 student veterans at the university.[29]

AVC Chapter 341 wrote a letter to President Marvin calling for racial discrimination at Lisner auditorium to end. In another anticlimactic response, Marvin kicked the issue down the road, stating he would bring the matter up to the university’s Board of Trustees at their next meeting on December 12. With the delay, GW dug its hole deeper.[30]

Other institutions began taking stock of their racial guidelines in light of the growing attention paid to GW and Lisner. The National Symphony Orchestra, for example, moved their students’ concerts from Lisner to Constitution Hall, stating that all children (no matter the color of their skin) had the right to access their performances.[31] Thirty–three members of the Dramatics Guild vowed not to bring any of their upcoming shows to the nation’s capital unless all persons were permitted to attend.[32]

Meanwhile, student activists ratcheted up the pressure. In early November, black students from Howard University joined white GW students and attempted to attend a student theater show at Lisner. Theater staff turned away the Howard students, further calling attention to the school’s racist policy.[33]

The issue of segregation at Lisner auditorium was at a roaring boil by the start of the spring semester in January 1947. There was no good way to frame the events of the previous few months to look like anything other than an issue of race discrimination. In a time and city with shifting beliefs around segregation, sticking to a whites only policy at Lisner Auditorium seemed ill-advised. It was not only unjust, it was bad business. After pushing the issue off at the December meeting of the Board of Trustees — perhaps in the hopes that the problem would blow over with time — the board finally addressed segregation at Lisner during their February meeting.[34]

“University classes and affairs are and will continue to be the principal use of the auditorium,” the Board’s statement read. However, it went on to say that when not being used for school activities, the hall “may be opened for lease to outside organizations for meetings or functions of a general educational nature” and that GW would impose “no restrictions on attendance” of those events.[35]

Advocates for desegregation immediately praised the university’s decision. As Ida Fox, executive director of the Committee on Racial Democracy told The Evening Star:

It’s fitting that an institution of higher learning should take the leadership in erasing barriers that arbitrarily stand between the Negro and his elementary rights as a human being and a citizen in a democracy… We hope the university will continue to chart new paths in this direction, and we hope also that the National Theater will take note and follow suit.[36]

After nearly five months of fighting, civil rights advocates had forced the University to adopt a more equitable policy. It certainly seemed to be a victory... right?

Well, not exactly. There was one major caveat to GW’s new policy: Lisner would no longer be leased for commercial theatrical productions.[37] So, under the new policy, shows like Joan of Larrain could no longer be performed there.[38] In effect, rather than open up D.C.’s newest theater space to all-comers, the school chose to cut out commercial theater shows altogether, thereby reducing all Washingtonians’ access to professional theater.

Furthermore, even though the Board of Trustees said they would not police who came into the theater while it was leased out to organizations “for meetings or functions of a general educational nature,” evidence suggests that race was a factor in deciding what groups could lease the space. For example, the choir from historically black Howard University was denied, but a choir from a historically white school, Duke University, was allowed to use Lisner.[39] GW similarly turned away the prestigious African American Zeta Phi Beta Sorority.[40]

In 1948, Washington Post theater critic Richard Coe called out GW for its inconsistency with respect to use of Lisner: “The University has employed sliding rules for hospitality since its announcement, in 1946, that it planned to make its auditorium ‘a community center of cultural and intellectual enlightenment.'”[41] Notably, he also pointed out that the ban on commercial performances had continued to be selective. Despite the board’s 1947 policy change, certain commercial theater companies had been permitted to use the space while others were turned away.[42]

Happenings beyond campus made GW’s inconsistent stance even more dire for Washington’s theater scene. A few blocks away, the National Theatre decided to shut down in the summer of 1948 rather than integrate audiences, a major blow to performing arts in Washington. Coe urged GW to adopt a more consistent and open policy at Lisner for the benefit of the city. “It looks virtually certain that there will be no theater next fall in the Capital of the most powerful Nation on earth…. George Washington University has it in its power to give shelter to the art.”[43] The critic added, “If President Marvin, as one of this community’s leaders, should offer to step into this breach caused by the closing of the National, it would do much to clear the university’s unhappy role in the recent past.”[44]

So did the school seize the opportunity? Not really, it seems. The school apparently continued its selective policies — and permitted those who leased Lisner for private events to restrict audiences — for several more years.[45] Change at the theater happened in earnest after GW began admitting African American students in 1954 — the last university in D.C. to do so.[46]

Like so many other episodes in Civil Rights history, the path toward equity at Lisner was full of small steps forward, pushback, and contradictions. While desegregation of the theater was not the immediate victory many advocates envisioned in February 1947, it's safe to say it pushed the conversation about race forward in Washington.

Footnotes

- ^ “Opinion in the Capital” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 31, 1946.

- ^ “Lisner Auditorium,’” events-venues.gwu.edu, the George Washington University, accessed June 22, 2022 and Robert E. Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theaters,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC) October 29, 1946.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “… And Lisner?” Auditorium Discrimination Folder, Cloyd H. Marvin Correspondence Files, The George Washington University Special Collections Research Center, The George Washington University Libraries, Wash;ing ton, DC.

- ^ Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theaters.”

- ^ “Letters to the Star: Readers Continue Their Debate of Race Discrimination,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 6, 1946.

- ^ McQuirter, Marya Annette, "A Brief History of African Americans in Washington, D.C.," Cultural Tourism DC, accessed August 5, 2022. The Reconstruction-era Civil Rights Acts of 1872 and 1873 further differentiated the District from other areas of the country. Those laws, which were never rescinded, decreed that segregation had no legal standing in D.C.'s public places. However, they were omitted when the District Code was rewritten in the 1890s. See Andrew Novak, “The Desegregation of George Washington University and the District of Columbia in Transition, 1946–1954,” diversity.Smhs.gwu.edu, the George Washington University, accessed June 23, 2022.

- ^ “Race Issue Threatens to Close National Theater Before Jan.1.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 14, 1946.

- ^ Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theaters.”

- ^ “‘Community Policy?”’ Auditorium Discrimination Folder, Cloyd H. Marvin Correspondence Files, The George Washington University Special Collections Archives, Gelman Library.

- ^ G.W. Auditorium Barring of Negroes Protested,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 10, 1946.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Associated Press, “‘Race Problem Local Producers Asserts,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 20. 1946.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Veteran Club Filed Complaint,” GW Hatchet (Washington, DC), November 7, 1946.

- ^ “Lisner Auditorium,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), October 31, 1946.

- ^ Craig Simpson, “DC’s Old Jim Crow Rocked by 1939 Marian Anderson Concert,” Washingtonareaspeaks.com, Washington Area Speaks, accessed July 29, 2022.

- ^ “Veteran Club Files Complaint.”

- ^ Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theaters.” And Robert Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theater, The WashingTon Post (Washington, DC), October 29, 1946. And “Robert Emmet Sherwood,” Wikipedia.com, Wikipedia, accessed June 22, 2022.

- ^ Sherwood, “Jim Crow Theaters.”

- ^ “Letters to The Star Readers Continue Their Debate of Race Discrimination.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Theater Racial Ban: Opinion in Capital Is Sought in Survey,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 31, 1946.

- ^ “G. W. Veterans' Unit Lays Expulsion Move to Its Racial Policy,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC),, November 16,

- ^ Ibid. And “In a Stormy Session,” GW Hatchet (Washington, DC), November 14, 1946.

- ^ “… And Lisner?”

- ^ “Lisner Auditorium Concerts Shifted because of Race Issue,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 8, 1946.

- ^ “… And Lisner?”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Decision Postponed on Lisner Race Policy,“ The Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 13, 1946. And “G.W. Lifts Racial Ban at Lisner but Limits Use of Auditorium,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 14, 1947.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “G.W. Lifts Racial Ban at Lisner but Limits Use of Auditorium.”

- ^ “G.W. Lifts Racial Ban at Lisner but Limits Use of Auditorium.”

- ^ “Racial Committee Hails G.W. Ruling on Meetings,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 15, 1947.

- ^ Richard L. Coe, “G.W., Theater Guild, or Olney Could Rescue Our Theater: How to Save Our Theater,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), July 4, 1948.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Simpson, “DC’s Old Jim Crow Rocked by 1939 Marian Anderson Concert.”

- ^ Novak, “The Desegregation of George Washington University and the District of Columbia in Transition, 1946–1954.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)