From the Mixed-Up Files of the Smithsonian Museum of American History: The Heist of 1981

On a cold, overcast Tuesday morning in February 1981, something caught the eye of a museum technician as he walked through the “We the People” exhibit on the second floor of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History: The silver pen of President McKinley’s Secretary of State John Hay was missing.1, 2 The 7 ¼-inch Parker Jointless pen had been used to sign the 1898 Treaty of Paris, ending the Spanish-American War.3

But now, to the technician’s horror, its case was empty.

The pen had been photographed for a book on the museum in the days prior. As museum staff and federal agents tried to reconstruct the events leading to the disappearance of the pen, they deduced that it must have been spirited away sometime after the photography session. It was never returned to its case.

For Smithsonian staff, the theft brought back a sinking feeling that had become depressingly familiar. Over the previous few years, the Smithsonian Institution, and the American History Museum in particular, had been dealing with alarmingly high rates of silver theft; in 1978, the U.S. News and World Report estimated that 130 silver objects, including a cream pitcher believed to have been made by Paul Revere, had been removed from the institution’s storerooms.4

The allure of silver – and, it seems, silver theft – had skyrocketed when brothers Nelson, William, and Lamar Hunt became infamous after their failed attempt to corner the silver market through offshore hoarding. Their manipulations propelled the price of silver from $11/ounce in September 1979 to almost $50/ounce by January 1980.5 The price of gold also spiked in January 1980, surging to over $800 per ounce.6 By the time the John Hay pen went missing the next year, the prices had dropped considerably but it seems that thieves had taken note – there was still a lot of money to be made in precious metals. Indeed, the Metropolitan Police had noticed a big uptick in the theft of jewelry and silverware across the city in the months following the spikes.7

The FBI became involved with the investigation the same morning the pen went missing. The agency – in cooperation with Metropolitan Police – was already reacting to the sharp rise in burglaries with Operation Greenthumb. The investigation, which would become public a few months later, targeted fences – gold and silver dealers who traded in the market of stolen items. They often paid burglars pennies on the dollar and then re-sold the goods for immense profit, or had them smelted down. As far as the pen was concerned, “Logic would point toward an inside job of some kind,” according to FBI special agent Larry Knisley.8 But there were no suspects – at least not yet.

The American History Museum was at a particularly vulnerable point in its life cycle in the early 1980s. Secretary S. Dillon Ripley had appointed a new museum director, Roger G. Kennedy, who not only renamed the museum, but was “determined to follow an entirely different approach,” according to David Allison and Hannah Peterson in their 2021 book, Exhibiting America.9 Kennedy’s approach involved a complete overhaul of the second floor of the museum, among other sweeping changes, including a redesign of the Flag Hall.

This time of transition was marked by notable internal disorganization and disarray at the museum. With large exhibits closed for remodeling and artifacts coming in and out of storage, some details were bound to slip through the cracks.

By the time the John Hay pen disappeared, a guard by the name of Vincent Butler Whitley had been working at the museum for seven years, hired when he was only 19 years old. As the winter of 1981 heaved its final breaths, the days were only getting drearier and Whitley was surrounded by countless silver and gold objects at the Museum of American History. Was he tempted? Apparently so.

On March 6th, about a month after Hay’s pen went missing, another discovery rocked the Museum. The Armed Forces Hall had been pillaged: two swords and two medals were missing from its Naval History wing. To wit:

- a $35,000 gold- and diamond-encrusted sword presented in 1883 to Commodore James Biddle by the Viceroy of Peru;

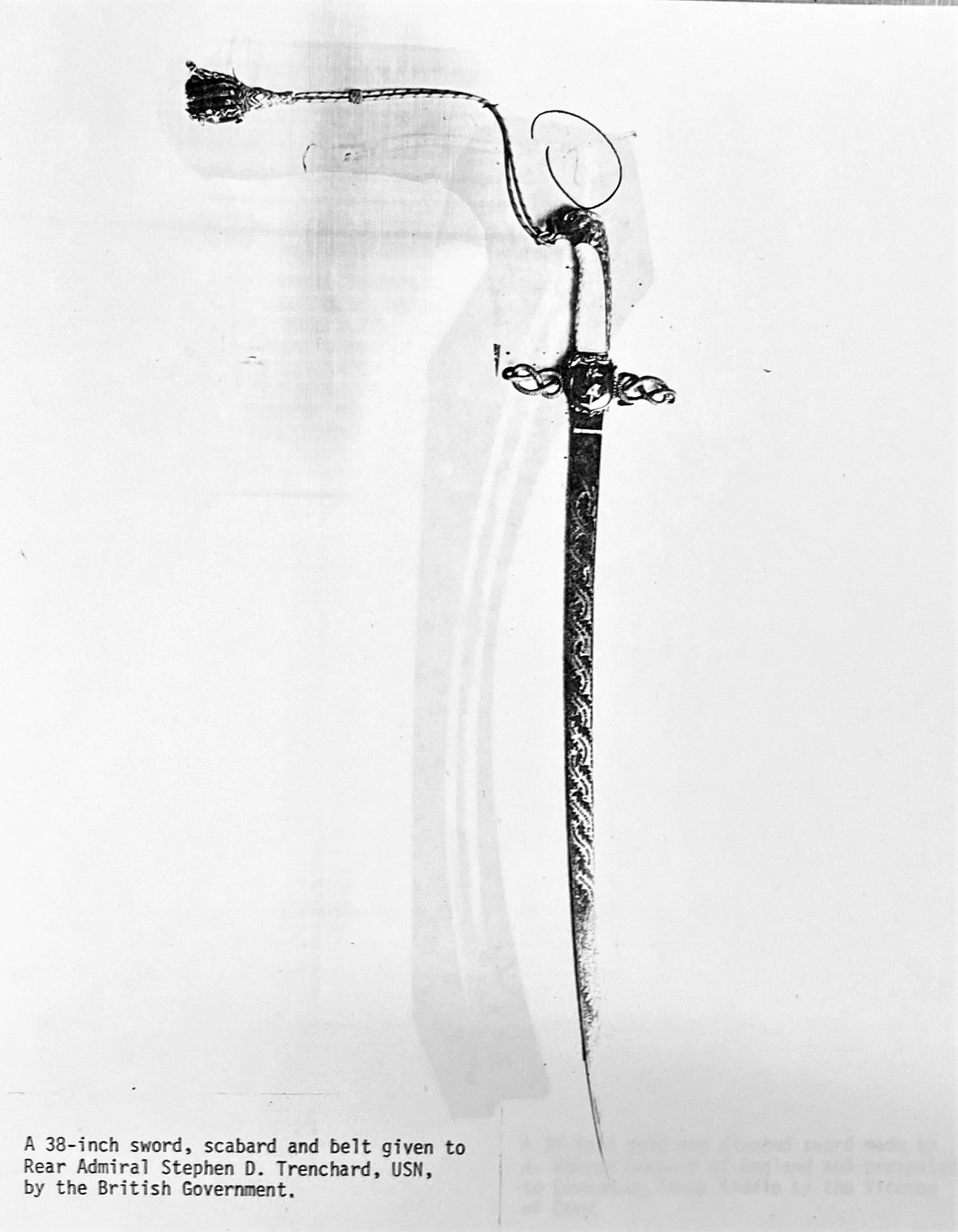

- another with an ivory hilt valued at $15,000, presented to naval hero S. Decatur Trenchard in March 1885;

- a medal awarded to Navy LT. John Guest for laying the first trans-Atlantic telephone cable;

- and one awarded to Navy Capt. Charles Wilkes by Britain’s Royal Geographic Society following his discovery of Antarctica.

In total, these artifacts were valued at $77,000.10

The FBI’s initial examination of the Naval History crime scene revealed signs of forced entry on the tops seven-foot-tall display cases. They concluded that the perpetrator had climbed a ladder and removed a plastic light cover to cut through a wire mesh using an “edged instrument.”11 The FBI also concluded that the four swords and medals were stolen on four separate occasions.12 Why the missing objects were not noticed as they were being taken is only further testament to the internal chaos of the museum at the time.

Technicians at the museum had seen these thefts coming from a mile away, and had been desperately trying to sound the alarm, no one more vociferously than Joseph Young. Young’s first memo begging for updated security equipment in the Naval History wing dated back to March 1st, 1980. “It has been brought to my attention that the present alarm and glass may not be adequate to serve today’s security needs,” he wrote.13

Nobody did anything, and the thefts continued. So did Young’s memoranda: “If this had been done when requested, we would not now be replacing objects we are now replacing.”14

Six days after the discovery of the missing swords and medals, Young fired off yet another memo, requesting the security upgrade. “The case is presently empty…,” he pointed out with a note of sarcasm, “thus making it accessible to your staff.”15 The exhaustion in his tone was unmistakable.

As the FBI investigated the case, the bureau became increasingly convinced that the robber was intending to melt down the artifacts – or sell them to a fence who would melt them. The theory made sense. Finding a collector who was willing to buy stolen historical objects – and pay top dollar for them on the basis of their historical importance – was likely beyond the reach of most thieves. As Smithsonian spokesman Lawrence Taylor told the press, “While it is of great intrinsic value, the pen would be virtually worthless to a thief, because it has no inscription or accompanying documentation to describe its historical significance.”16

Fencing and smelting – melting down metals – offered an attractive alternative, though it came with its own challenges. As FBI spokesman Bob Golden noted “melting down [artifacts] is a sophisticated plot and you have to have a lot of contacts for that.”17 But, as the Operation Greenthumb investigation demonstrated, there were plenty of fences around D.C. that were willing to help, for a price.

The Bureau began its search for the thief inside the museum: it was a well-recognized fact among museum officials and detectives that “behind-the-scenes thievery” is, more often than not, the likely explanation for disappearing artifacts.18 According to a 1978 U.S. World and News Report article, “Many experts are convinced that the toll from administrative stealing is huge.” Unfortunately, this is a incredibly hard statistic to prove, because “most inside jobs are never reported”19 but past ‘inside jobs’ at the Smithsonian had been attributed to museum staff or volunteers.20

On May 7th, 1981, as a result of anonymous insider information provided to the FBI, the bureau arrested three D.C. men in connection with the disappearance of the swords and medals: guard Vincent Butler Whitley, his first cousin, a 33-year-old Watson Lewis Mills Jr., and a third man by the name of Ronald Conrad Pugh.21 Pugh was arrested at the DC Superior Court, where he was appearing in an unrelated matter.

Details on how the trio pulled off the theft are sketchy but based on news reports from the time, it seems likely that Whitley stole the items during his shift and then worked with his cousin and Pugh to sell the artifacts to a fence. According to the Washington Post, “The FBI alleged that Whitley received $200 as a partial payment from Mills, his cousin, and had an agreement to split the proceeds after Mills and Pugh disposed of the stolen objects.”22 The arrested men were suspected responsible for the theft of the John Hay pen as well, but that investigation remained ongoing.23

In the weeks following the May 1981 arrests, the Trenchard and Biddle swords, as well as the silver John Hay pen, were recovered from Maryland smelters. Jewels had been removed and the objects had suffered damage, but they had not yet been melted down. Receipts showed that the pen, which had been appraised at $25,000 in 1973, had been sold to the smelting operation for a mere $25.24 Whitely pled guilty to one count of theft of government property — James Biddle’s gold- and diamond-encrusted sword — on July 29th, 1981. He was sentenced to two years of probation.25 By August 1981, the FBI returned the artifacts to their rightful home at the Museum of American History.26

The arrest and recovery marked a rare victory in the war on inside theft at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. But museum officials didn’t have to wait long for a reminder that the problem of theft was a constant battle.

Just a month after Whitley and his associates were brought to justice, George Washington’s gold and ivory dentures disappeared from a locked fifth-floor storeroom, where they were being kept in advance of the museum’s celebration of his 250th birthday.27 Technicians later found one of the plates in storage, but the other was never recovered. It was a “humiliating blow”28 to the NMAH – especially when museum officials admitted that they could not be sure how long the dentures had been gone before they were discovered missing.29 30

The fall of 1981 saw reforms that would reshape the Smithsonian’s approach to security and storage. A dramatic increase in the Office of Protection Services budget — $2.1 million dollars31 — was used to institute rigorous background checks for staff and to purchase equipment for the new Museum Support Center, a facility in Silver Hill, Maryland designed to keep artifacts in storage more secure.32

Footnotes

- 1 Michael D. Davis, “FBI Charges Guard, Two Others In Theft of Smithsonian Artifacts,” Evening Star, May 8, 1981.

- 2 Roger Piantadosi, “Historic Pen Used to Sign Treaty of Paris Missing From Smithsonian,” Washington Post, February 14, 1981.

- 3 Davis, “FBI Charges Guard, Two Others In Theft of Smithsonian Artifacts.”

- 4 “Museums Fight Rising Toll Of Inside Theft” (U.S. World and News Report, May 1, 1978.), Record Unit 360 / Box 31, Smithsonian Institution Archives. Thefts were not limited to the Museum of American History. In 1979, a $25,000 bejeweled snuff box belonging to Catherine the Great was lifted from the National Collection of Fine Arts (see Washington Post article “Four Objects Stolen From Smithsonian”).

- 5 Time. “Nation: He Who Has a Passion for Silver,” April 7, 1980.

- 6 History.com Editors. “Gold Prices Soar.” History.com.

- 7 Joe Pichirallo and Ron Shaffer, “‘Operation Greenthumb’ Rakes in Fencing Suspects,” Washington Post, April 29, 1981.

- 8 Roger Piantadosi, “Historic Pen Used to Sign Treaty of Paris Missing From Smithsonian,” Washington Post, February 14, 1981.

- 9 David Allison and Hannah Peterson, Exhibiting America: The Smithsonian’s National History Museum, 1881-2018 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2021). Pg. 178.

- 10 “Smithsonian Stolen Items Recovered,” Evening Star, originally published by Associated Press, May 29, 1981.

- 11 “‘Theft of Gold Coins & Two Swords:’ Memo from James McGuire in Reply to John F. Jameson,” March 9, 1981, Record Unit 477 / Box 38, Folder 3-4-5-4, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

- 12 “Smithsonian Stolen Items Recovered.”

- 13 “Memos from Joseph Young to John White,” March 1, 1980, Record Unit 383 / Box 9, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

- 14 Ibid.

- 15 Ibid.

- 16 Piantadosi, “Historic Pen Used to Sign Treaty of Paris Missing From Smithsonian.”

- 17 “Stolen Smithsonian items Recovered.”

- 18 “Museums Fight Rising Toll Of Inside Theft.”

- 19 “Museums Fight Rising Toll Of Inside Theft.”

- 20 Henson, Pamela M. “Crime at the Smithsonian Institution.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, Institutional History Division, n.d. See also “Museums Fight Rising Toll Of Inside Theft.” U.S. World and News Report, May 1, 1978. Record Unit 360 / Box 31. Smithsonian Institution Archives.

- 21 “Smithsonian Stolen Items Recovered.”

- 22 Pichirallo, Joe, “Smithsonian Guard, 2 Other Men Charged With Thefts at Museum,” Washington Post, May 8, 1981.

- 23 Michael D. Davis, “FBI Searches for Stolen Items,” Evening Star, May 8, 1981.

- 24 Ally Schweitzer, “The Art of the Steal: A Brief History of Museum Theft in D.C.,” Washington City Paper, January 15, 2014.

- 25 “SI Guard Arrested and Sentenced for Theft,” History of the Smithsonian Catalog, May 7, 1981.

- 26 “FBI Returns Stolen Items to NMAH,” History of the Smithsonian Catalog, August 19, 1981.

- 27 Allison and Peterson, Exhibiting America. Pg. 222.

- 28 Paul Clancy, “Set of Washington’s False Teeth Reported Missing by Smithsonian,” Evening Star, June 20, 1981.

- 29 Clancy, “Set of Washington’s False Teeth Reported Missing by Smithsonian.”

- 30 “George Washington’s False Teeth Stolen,” The Torch: A Monthly Newspaper for the Smithsonian Institution, July 1981.

- 31 Schweitzer, “The Art of the Steal.”

- 32 “Smithsonian Year 1981: Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ended September 30, 1981.” City of Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1982.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)