“What Hath God Wrought:” The Long Road to Washington’s First Telegraph

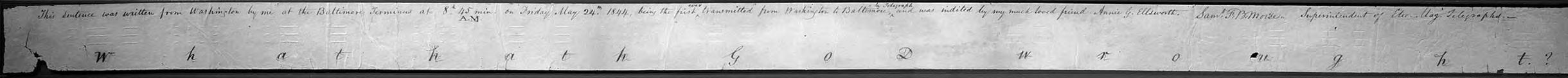

Good students of history may know that the first telegraph message tapped out in the United States was an exciting yet ominous “What hath God wrought?” Sent by Samuel Morse in the Capitol to his associate Alfred Vail in Baltimore on May 24, 1844, the message seemed to break open a new technological horizon. As one reporter noted at the time: “This is indeed the annihilation of space.”1

But the aptly chosen “What hath God wrought” was not the first telegraphed message to leave the Capitol, nor was it even the first display of the technology to the public. In fact, the famous message came about towards the end of a seven-year process in which Morse tried to sell Congress on the utility of a communications revolution.

Better known as an artist than a scientist, Samuel Morse had been developing his telegraph for five years by 1837. That year, Levi Woodbury, Secretary of the Treasury, announced the department would accept proposals for a telegraph system like those being developed in France and England. Plans flooded in, almost all of them on a French model called the optical telegraph (a network of towers in which operators flashed lights in code at each other). One stood out from the rest: an artist from Massachusetts offering what he called an “electromagnetic telegraph.”

Congress was interested. They invited Morse to Washington. In an era where “it was not an uncommon thing for inventors of all kinds of outlandish and impractical machines to hang around the Capitol buttonholing every senator and member they could meet,” Morse endeavored to prove his telegraph was worth their attention—and their money.2

In 1838, Morse demonstrated the telegraph in the meeting room of the House Commerce Committee. His audience included “representatives, senators, cabinet secretaries, and President Martin van Buren.”3 While the machine seems to have worked, the Panic of 1837 had sunk America into a depression and Congress couldn’t justify handing Morse thousands of dollars to test his theories.

But the meeting wasn’t fruitless: the Commerce chairman, Francis O.J. Smith, became enamored with the telegraph’s potential. In fact, he liked what he had seen so much that when he lost reelection later that year, he became Morse’s business partner, publicist, and agent. This relationship would sour in the future, but for now Francis Smith became Morse’s powerful Washington ally.

Morse returned to the Capitol in 1842. This time, he set one receiver in the House Commerce Committee room, and another in the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs. With wires strung between the two rooms, he demonstrated his telegraph again. This time, the Commerce Committee was impressed enough to send a bill allocating $30,000 to test the “capacity and usefulness” of Morse’s telegraph on a scale not just between committee rooms, but between cities.4

However, even with committee approval, the bill was not popular. On the House floor, Representatives mocked the idea that Morse’s telegraph would work over long distances. One suggested they establish a telegraph line to the moon. Twenty-two Representatives voted to add funds to the bill to study Millerism, a fringe religious group.5 By only six votes in the House and only hours before the Senate recessed, Congress approved the funding.

The project would be an underground telegraph line, with 160 miles of wire laid in 70,000 pounds of insulated lead pipes between two major cities.6 It was essentially a proof-of-concept; in 1842, Morse had laid a wire across New York Harbor and successfully activated it. This would be the first test of the telegraph between two cities.

Morse’s first task was determining where to lay his line. His first choice was New Jersey, whose railroad shot him down for fear a telegraph would create business “done by wire rather than by rail.” The Baltimore & Ohio railroad was more amenable. They would let Morse lay 38 miles of wires from Washington to Baltimore, so long as it would be done “without injury to the road and without embarrassment” to the company, reserving the B&O’s rights to use the line free of charge. They would also allow Morse’s work crews to pay half-fares—but only for passengers. Equipment and freight would remain full price.7

Francis Smith was equally delighted with the funding. As Morse’s business partner, he immediately sought out business partners. He recruited engineer Ezra Cornell, who created a special plow to lay the wires. He also negotiated the contracts for laying the pipes—with a company conveniently owned by his brother-in-law.8 When the contracts arrived, Morse balked at the prices.

“I have taken a pride in showing the Government how cheaply the Telegraph could be laid,” he wrote Smith in May. Morse knew “plenty of other applicants” would do the work “for much less.” But he acquiesced that he would “do nothing in regard to the matter until I see you.”9

Perhaps exercising some of his politicking experience, Smith assuaged Morse’s concerns: the prices were not renegotiated, and Smith remained the executor of the contract.

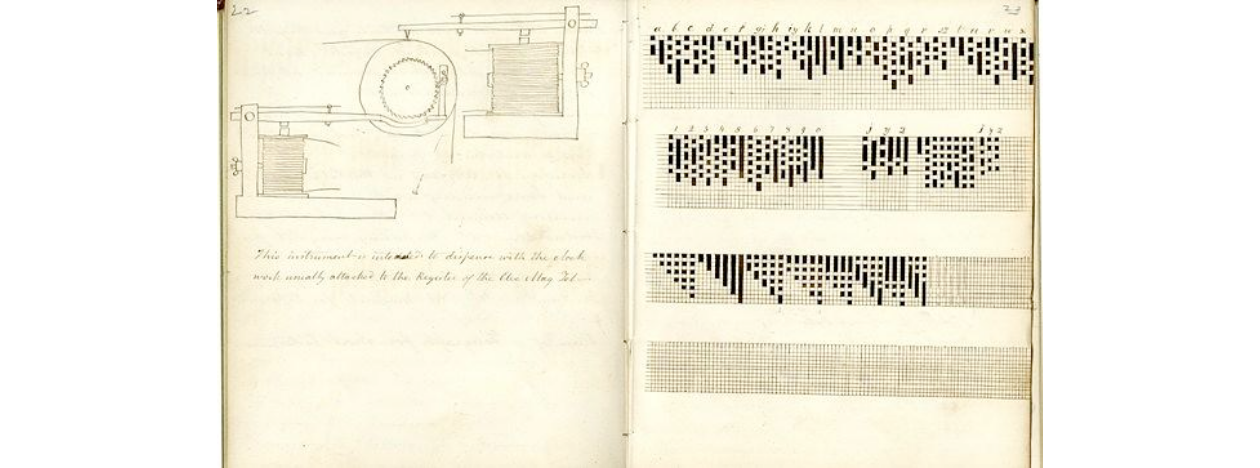

For a while, construction went smoothly: Cornell’s plow made a trench along the road, the insulated wires and pipe were laid, and an attachment at the back of the plow covered them up again. Morse also invited Alfred Vail to the project, who had already collaborated with Morse on components of the telegraph (including vast improvements on what came to be known as Morse code). But in December, when the line was only nine miles from Baltimore, the team discovered a problem that stopped construction in its tracks.

The pipes, which Francis Smith had helped procure, were defective.

The wires had been inserted into the leaden tubes too quickly during the manufacturing process. Without time to cool, the pipe itself charred or melted the insulation of the wires, and they were no longer conducting charges. It was disastrous news: with half of his appropriation already spent and the pressure to deliver mounting, Morse was sent back to the drawing board.

Not only that, but it seemed Francis Smith was showing his true colors. “The trenching is stopped,” Morse wrote. “And has brought the contractor upon me for damages.”

A belligerent Smith wrote to the Treasury complaining that Morse violated their contract and threatened to sue for lost profit. The betrayal injured Morse and only distracted him from more pressing issues. Angered, he wrote to his brother: “Where I had expected to find a friend I find a FIEND.”10

With dwindling funds, Morse took the winter to reassess. Until March, he could blame the stalled project on the weather. Cornell suggested an idea that had been implemented in England: putting the wires in the air. They were not sure if it would work, but it was the fastest, cheapest option. Morse agreed. Fixing the pipes would create a “greater delay and expense… than to put the wire on posts.”11 They got to work designing the new telegraph poles.

By March 17, work on raising the wires had begun. Where the pipes had once lain, tall chestnut posts were erected. Each could hold four wires but for now had only two. To carry electric current over such distances, huge sheets of copper were buried at the ends: one under the Pratt Street dock in Baltimore, and another in the basement of the Capitol.12

Throughout April, Morse and Vail tested the line—at 7 miles, 10 miles, 16 miles, and 22 miles, the telegraph line remained strong.13 All the while, Smith continued his remonstrances against Morse for the failed contract. “[Smith] is a ruined man in reputation,” Morse wrote. Though he didn’t fear losing any lawsuits, Morse worried that his old business partner “may sink the Telegraph also in his passion.”14

By the end of April, the line had reached Annapolis Junction, still 16 miles from Baltimore. The Whig Convention was expected to announce their candidate for president on May 1. Morse saw this as a perfect chance to show the telegraph’s utility: when the Baltimore train passed through, Alfred Vail would get the latest news from a passenger, then telegraph it to Morse. If all went well, the news in Washington would arrive before the convention’s attendees did.

Morse and Vail had already practiced in the days prior, to great effect “Your message today that ‘the passengers in the cars gave three cheers for Henry Clay’ excited the highest wonder in the passenger who gave it to you… when he found it verified at the Capitol,” Morse told Vail.

Before May 1, Morse sent Vail to Annapolis Junction with these instructions:

Do not be out of hearing of your bell. When you learn the name of the Vice Prest. nominated, see if you cannot give it to me, and receive from me an acknowledgment of its receipt before the cars leave you … It may be well to have an evening trial on some dark and perhaps foggy night, to show the independence of the Telegraph on the weather… Do not forget to keep your circuit closed after writing.

He also reminded him to “correct your error of running your letters together.”15 Either from nerves or excitement, Vail seems to have had a habit of sending transmissions too quickly. At the time, Morse’s telegraph marked out long and short dashes on a strip of paper instead of audible beeps, so squished symbols could be difficult to decode.16 For the demonstration, everything had to go perfectly.

On May 1, 1844, Morse and Vail telegraphed “all day.” When the Baltimore train paused at the station, Vail notified Morse that the Whigs had nominated Henry Clay. For the first time, news from Baltimore arrived ahead of the train—by sixty-four minutes!17

When the passengers arrived in the capital with the latest news from Baltimore, “they heard the newsboys shouting their extras and saw there in cold print their supposed information.” It was astonishing. The passengers “had no belief that little instrument they saw at Annapolis [Junction] beat them in carrying the news to Washington.”18

But beat them it had, and would continue to do.

Finally, by May 24, the telegraph line had reached Baltimore. An audience of Congressmen waited with hushed anticipation in the dim light of the Old Supreme Court chamber in the Capitol as Morse tapped out the famous message, “What hath God wrought?” With his own audience around him in Baltimore, Vail returned the same message just moments later. The phrase was selected by Morse’s friend Annie Elsworth from the biblical Book of Numbers, knowing that the inventor was a devout Christian.

In case that had not been enough, Morse got one more chance to prove the telegraph’s utility. The Democratic National Convention convened in Baltimore “most opportunely” (in Morse’s own words) only days afterward. The Convention nominated Senator Silas Wright to the vice presidency. Still telegraphing from the Capitol, Morse ran to inform the Senator. He refused to accept the nomination, which Morse swiftly telegraphed to Baltimore. Only minutes after the nomination had been announced, it had been rejected—from forty miles away.

It all happened so quickly that the Convention adjourned for the day, alarmed and mistrustful of the news that had come tapping out of Morse’s telegraph. They sent a delegation to Washington by train to confirm Wright’s response, only to hear exactly what he had telegraphed them earlier: he would not be Vice President. Had they listened, they might have saved a day of travel!

On May 30, Morse delivered news of James Polk’s nomination to a crowd of several hundred Congressmen gathered on the Capitol lawn. “Three cheers were given to me,” he said, for the lightning speed of the news. A Representative who had mocked the telegraph back in 1843 approached Morse and said, “Sir, I give in. It is an astonishing invention.”19

Thus, America’s first telegraph line was laid, and its first messages delivered. The press fawned over the new invention, and the Baltimore-Washington telegraph line was opened to the public the next year with Morse as its superintendent. Despite the setbacks, Morse had constructed the line more cheaply than his peers in England: by Morse’s own reporting, English telegraphs were built at $662 per mile. His telegraph was constructed—not including the initial disaster with the underground pipes—at only $400 per mile.20 Just a decade later, the little Baltimore-Washington line would be just one part of 20,000 miles of cable crisscrossing America, connecting the swiftly expanding nation like never before and keeping Washingtonians up to date on the latest news from all over the country.21

Footnotes

- 1

New-York daily tribune. [volume] (New-York [N.Y.]), 27 May 1844. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 2

Senate.gov. “U.S. Senate: First Telegraph Messages from the Capitol,” May 2018.

- 3

Senate.gov. “U.S. Senate: First Telegraph Messages from the Capitol,” May 2018.

- 4 States, United. Acts and Resolutions Passed at the First [and Second] Session[s] of the Twenty-Seventh Congress of the United States. 1841. March 3, 1843. Sec. III, Ch. LXXXIV.

- 5 Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation’s First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford University Press, 1996.

- 6

Vail, Alfred. Early History of the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph: From Letters and Journals of Alfred Vail. New York City: Hines Brother, 1914.

- 7

Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation’s First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford University Press, 1996.

- 8 Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation’s First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford University Press, 1996.

- 9

Breese, Morse Samuel Finley. Samuel F. B. Morse, His Letters and Journals in Two Volumes,. Vol. 2. Hardpress Publishing, 2016.

- 10

Breese, Morse Samuel Finley. Samuel F. B. Morse, His Letters and Journals in Two Volumes,. Vol. 2. Hardpress Publishing, 2016.

- 11

Breese, Morse Samuel Finley. Samuel F. B. Morse, His Letters and Journals in Two Volumes,. Vol. 2. Hardpress Publishing, 2016.

- 12

Hungerford, Edward. The Story of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, 1827-1927, 1928.

- 13

Vail, Alfred. Early History of the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph: From Letters and Journals of Alfred Vail. New York City: Hines Brother, 1914.

- 14

Breese, Morse Samuel Finley. Samuel F. B. Morse, His Letters and Journals in Two Volumes,. Vol. 2. Hardpress Publishing, 2016.

- 15

Breese, Morse Samuel Finley. Samuel F. B. Morse, His Letters and Journals in Two Volumes,. Vol. 2. Hardpress Publishing, 2016.

- 16

The Library of Congress. “Invention of the Telegraph.” Accessed April 20, 2024.

- 17

PBS. “The Great Transatlantic Cable.” American Experience, June 4, 2019.

- 18

Byrne, Michael. “‘What Hath God Wrought’: Not Quite the First Telegraph.” Vice News, May 24, 2011.

- 19 Dilts, James D. The Great Road: The Building of the Baltimore and Ohio, the Nation’s First Railroad, 1828-1853. Stanford University Press, 1996.

- 20

Dept. of the Treasury to the 28th Congress. The report of Prof. Morse announcing the completion of the electro-magnetic telegraph between the cities of Washington and Baltimore. June 6, 1844.

- 21

Mullen, Matt. “Samuel Morse Demonstrates the Telegraph with the Message, ‘What Hath God Wrought?’” HISTORY, July 20, 2010.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)