A Free Black Preacher from Maryland Wrote a Song That Changed History

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the U.S. government initiated a series of public relief organizations that provided work to skilled laborers who lost their jobs. One such organization was the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), established in 1935. Designed to aid thousands of struggling American writers and journalists, the projects commissioned by the FWP ranged from local histories to children’s books and travel guides.1 But perhaps their most interesting project is also one of their most important: their collection of oral histories known as the “Slave Narratives Project.”

Between 1936-1938, in order to preserve a history that was in danger of being lost to time, FWP writers interviewed over 2000 Black Americans who experienced slavery in some way. Most were enslaved themselves and, despite their advanced age, could clearly recall the horrors they experienced in their youth. The result is an unparalleled insight into the lives of enslaved people in their own words.2 The interviews are harrowing, poignant, and often unflinchingly graphic. FWP writers travelled through both Maryland and Virginia collecting stories, so DMV residents are given a unique opportunity to learn more about historic Black experiences in our area.

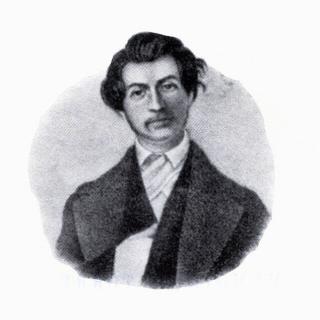

There are many incredible stories told in these volumes, but one of my favorites is the story of Rezin Williams: a preacher born in Prince George’s County who might have written a song that changed history. Rezin (sometimes spelled “Reason”) Williams was interviewed at his home in Baltimore in September 1937. He claimed to be 115 years old, born in 1822, but this is inconclusive—official records show a variety of possible dates, most likely in the 1830s, so it’s possible that Williams himself didn’t even know his exact date of birth and chose one for himself.3 Regardless, Williams was an elder in his community, perhaps the oldest surviving Black veteran of the Civil War at that time, whose vast life experiences earned him much respect. The interviewer declared that “there is perhaps nowhere to be found a more picturesque and interesting character.”4

Williams was never enslaved himself but grew up on and around the plantations of Prince George’s County. He was born at Fairview Plantation, the home of the prominent Bowie family in what is now their namesake city—the historic Bowie house, which Williams knew well, still stands within the Fairwood housing development.5 William’s family, descended from both Black and American Indian ancestors, were free—his father was a laborer employed by the Bowie family to work at Fairview.

Through his eyes, we see that Bowie and Prince George’s County were far different from the suburb we know today. Williams remembered that his home, and the homes of the people enslaved at Fairview, were “cabins made of slabs running up and down,” which were “crudely furnished.”6 Perhaps most evocative are Williams’s experiences with the limitations of his personal freedoms—even as a freeman. “I didn’t know that colored people had a right to do anything—even eat or buy anything or sell anything,” he told The Baltimore Sun in another interview in 1933. “A man can’t be happy feeling like that, can he?”7 Williams was allowed to leave Fairview and travel the county, hiring himself out on various farms, but it was extremely dangerous for him to do so. Fairview Plantation was located off the Annapolis Road (Route 450 today), a major thoroughfare between Annapolis and Washington that was regularly patrolled by bounty hunters. In the 1840s and 1850s, when abolition movements encouraged enslaved people to emancipate themselves, bounty hunters expected a standing reward for the capture of runaways—or anyone they perceived to be a runaway. Williams recounted one harrowing experience with such “patrollers” that almost cost him his life:

“Once before the war, I was riding Lazy, my donkey, a few miles from the boss’s place at Fairview, when along came a dozen or more patrollers. They questioned me and decided I was a runaway slave and they was going to give me a coat of tar and feathers when the boss rode up and ordered my release. He told them dreaded white patrollers that I was a freeman…”8

But Williams also described the hope and resilience that was at the heart of his community’s culture. Most important to them was their religion, since “the only times we ever had much fun” and could gather were at makeshift weddings, funerals, and other religious services.9 As a freeman, Williams had the chance to be ordained and become an important figure in his community, so he took it. “By special permission of plantation owners in Prince George’s,” Williams said, he was allowed to travel between the enslaved communities in the area and conduct informal services inside the quarters.10

Moved by his experiences and his faith, Williams began to compose his own spiritual songs in the 1840s. They are clearly inspired by that hope and resilience he encountered amongst the enslaved communities around him—but, interestingly, many are thinly-veiled allusions to freedom and self-emancipation. One of them even mentions Canada—a popular destination for those “riding” the Underground Railroad—as a safe haven without slavery, giving freedom seekers a tip.11 Another of William’s spirituals contains a very powerful message that made it extremely popular throughout Maryland. Here are some of the lyrics, as recorded by the FWP interviewer:

“When that there old chariot comes,

I’m going to leave you.

I’m bound for the promised land,

I’m going to leave you.

I’m sorry I’m going to leave you,

Farewell, oh farewell!

But I’ll meet you in the morning,

Farewell, oh farewell!”12

On surface level, this is a classic spiritual about death, mourning, and ascending to heaven. Look deeper, though, and you see the common thread running through William’s lyrics: a hope for freedom, a call for liberation, sorrow for leaving loved ones behind. It was so popular, its message so moving, that knowledge of the song must have spread throughout the state through the inter-connected network of Methodist preachers. This is probably how the song came to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where a young enslaved girl named Minty learned it during religious services. Later, Minty became known by the name she adopted after self-emancipation: Harriet Tubman.

According to the first biography written about her, published in 1886 and based on actual interviews, Harriet Tubman used William’s lyrics to bid farewell to her family just before her first escape in 1849.13 Not wanting the overseer to know her secret plans, Tubman chose a song that would communicate her sorrow, hope, and fear all at once—a message that could be understood when, suddenly, she was nowhere to be found. The lyrics recorded in the biography—which, again, was based on interviews conducted with Tubman herself—use William’s lyrics almost exactly, attesting to their widespread popularity even in the 1850s. Lucky for us, the 2019 biopic Harriet chose to dramatize this moment in Tubman’s story. The film’s composer, Terrence Blanchard, set William’s lyrics to new music and the song is sung powerfully by actress Cynthia Erivo. You can watch the scene here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrGrxa-fhKE

Williams continued to live in present-day Bowie until he enlisted for service in the Civil War. In the late 1860s, he made his home in Baltimore and lived there for the rest of his life with his wife and fifteen children.14 An active member of his community both as a preacher and activist, he clearly loved to speak about his many life experiences to anyone who would listen. He died in the late 1930s, shortly after his conversation with the FWP writer, at over 100 years old.15

Did Parson Williams know that his words had become such a powerful rallying cry for his people, especially for one of the most famous abolition activists of the nineteenth century? Since he doesn’t mention Tubman in his interviews, we’ll never know. Since Tubman was known to use spirituals as coded messages throughout her many dangerous journeys on the Underground Railroad, it’s possible that William’s words led others to freedom as well.

You can read the full interview with Williams, along with many other powerful stories of Black Marylanders, here in the Library of Congress collections: https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/

Footnotes

- 1

“The Federal Writers’ Project,” Forward with Roosevelt, The National Archives (14 July 2020), https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2020/07/14/the-federal-writers-project/

- 2

The FWP writers were instructed to record their interviews in dialect which perpetuated the racial stereotypes of the 1930s. The Library of Congress discusses the topic further online (https://www.loc.gov/collections/slave-narratives-from-the-federal-writers-project-1936-to-1938/articles-and-essays/note-on-the-language-of-the-narratives/ ). For the purposes of this article, direct quotes have been reinterpreted to rid them of this dialectical writing, but the originals can be viewed through the LoC collections.

- 3

“Rezin Williams,” in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census (Schedule 1: Maryland, Prince George’s County, Vansville, pages 44-45, line 8), Ancestry, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8054/

- 4

Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves 8 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1941), 69.

- 5

“Historic Fairview c. 1790,” Historic Homes Network, https://historichomesnetwork.net/property/historic-fairview-c-1790/

- 6

Slave Narratives 8, 71.

- 7

“Negro Patriarch Esteems Roosevelt Above Lincoln,” The Baltimore Sun (Baltimore: 20 March 1933), 3.

- 8

Slave Narratives 8, 75.

- 9

“Negro Patriarch Esteems Roosevelt Above Lincoln.”

- 10

Slave Narratives 8, 75.

- 11

Slave Narratives 8, 72.

- 12

Ibid.

- 13

Sarah H. Bradford, Harriet: The Moses of Her People (New York: George R. Lockwood and Son, 1886), 27-28.

- 14

“Negro Patriarch Esteems Roosevelt Above Lincoln.”

- 15

William’s exact date of death is unknown, but he does not appear in the 1940 U.S. Federal Census.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)