Women in Maryland and Virginia Were Valuable Fundraisers and Organizers for the American Revolution

Even though they may fall to the wayside of textbooks and curriculums, without the efforts women made toward the American cause in the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army would have been in dire straits indeed. Luckily, the women of America met the challenges of supply shortages, low morale, and lack of funds with determination and patriotism.

Two local women stand out in this history: Mary Digges Lee from Maryland, and Ann McCarty Ramsay from Virginia. Both had a personal relationship with George Washington and mustered enormous sums of money and supplies for the benefit of weary Continental troops.

During the Revolution, women found themselves confronting a new and uncertain landscape. The war upended previous political and social norms, providing a spate of new opportunities for women including “land ownership, political influence, paid work,” literary publication, further education, and financial authority.1 For enslaved women, the Revolution promised freedom via escape to British lines.

Women who supported independence organized boycotts of British imports, provided labor for Continental troops (usually for a wage or rations), and nursed soldiers. Women of greater means acted as diplomats, military liaisons, and organized drives for supplies and money. Martha Custis Washington famously threw fundraising balls for troops, entertained foreign diplomats, and corresponded with state authorities on her husband’s behalf.2

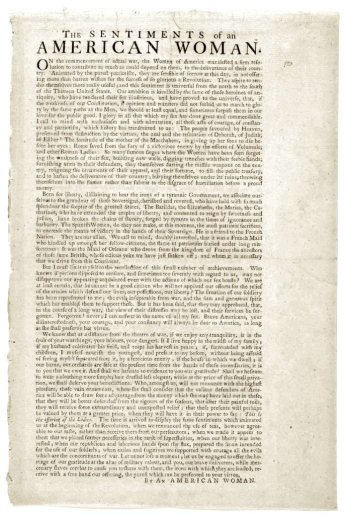

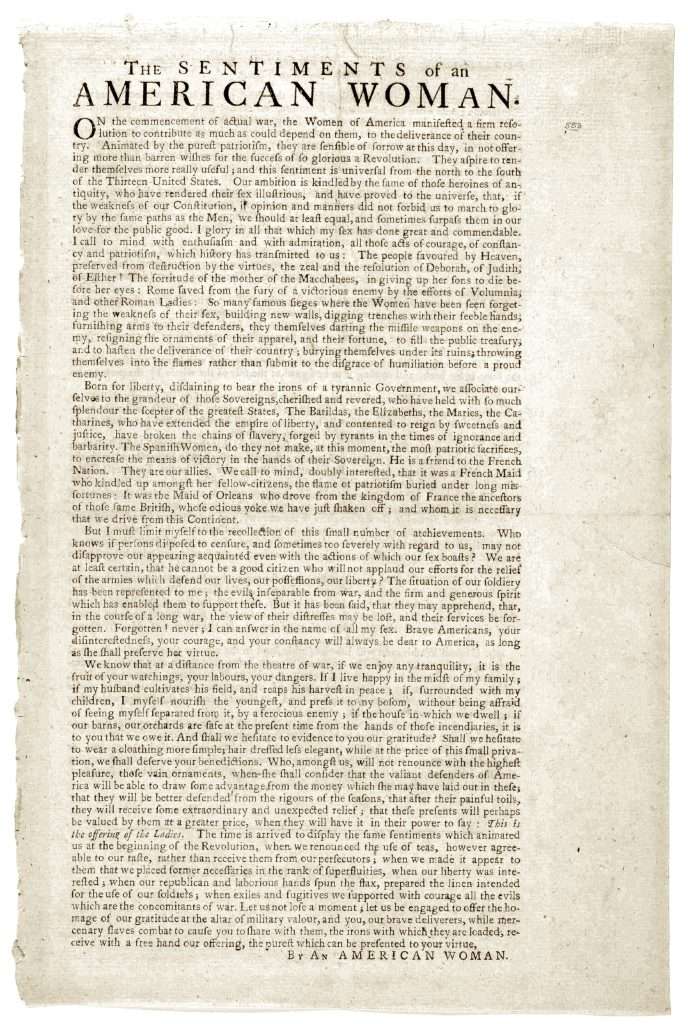

In larger cities, women created formal associations to raise funds, as Esther de Berdt Reed did in Philadelphia. She also wrote the broadside, Sentiments of an American Woman, which argued in support of the unprecedented steps women were taking into Pennsylvania’s public life and encouraged women in other states to do the same.

One notable fundraiser and organizer from Maryland was Mary Digges Lee, originally of Prince George’s County. Mary was born in 1745 on the 1,050-acre Digges family estate called Mellwood Park. Like other practicing Catholics, the Digges were shut out of formal politics for their faith but remained prominent and wealthy members of the Maryland aristocracy. They entertained members of the Colonial-era elite, including George Washington, who rested at Mellwood Park on long trips.3

Digges married the son of another prominent Maryland family, Thomas Sim Lee, who was soon elected Maryland’s governor in 1779. Now acting as Maryland’s First Family, Mary and Thomas were prominent supporters of the Revolution.

But Thomas faced steep demands and administrative challenges as Governor: he scrambled to find supplies for Maryland soldiers who lacked even basic necessities like “blankets, shoes, and tents.”4 Desertion rates skyrocketed as the brutal winter chill set in among the under-provisioned troops. In December 1779, General Washington wrote a personal appeal to Lee to scour his state for more supplies. He turned to his wife for help.

It was then that Mary Digges “enthusiastically stepped into the public arena.”5

This was shocking for a woman to do. In Colonial America, the accepted role of a middle- to upper-class woman was confined strictly to the home and domestic social sphere: she could be a wife, hostess, or homemaker, but not a political organizer or public advocate. Digges and other women challenged that assumption by leading the charge on the home front, often to great effect.

Digges rallied her social network among Maryland’s wealthy elite to raise funds. Women across the state were “daily depositing… Money in [her] hands.”6 In addition to monetary donations, she leveraged the time and talents of Maryland women in service to the cause of independence. When a plea went up for shirts for soldiers, she mustered the collective power of her donation network and delivered 260 linen shirts to soldiers from the Old Line State.7

On September 27, 1780, Digges wrote to George Washington: she had collected money but needed to know how to spend it and to whom she should send the proceeds. Soldier-like, she stated that she was entirely ready to “assist in the execution of your orders.”8

In a response to her letter, Washington directed Digges to purchase shirts and socks for troops with her money and enclosed “the warmest gratitude” of the soldiers she would help. As for Washington himself, he was “honored” by Digges’ work and expressed his “high sense… of the patriotic exertions of the Ladies of Maryland.”9

For her efforts, Digges was inducted into the Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame in 1995. She left a legacy not just as a First Lady of Maryland, but as a leader and organizer who “challenged contemporary popular notions of women's capabilities.”10

Another major fundraiser for the Revolution’s cause was Ann McCarty Ramsay, of Alexandria, Virginia. Ann was related to the Ball family, and therefore a cousin of George Washington through his mother, Martha Ball Washington. George remained a lifelong friend of the family; Ann’s son was a pallbearer at Washington’s funeral.

Ann had married William Ramsay, an import-export merchant and one of Alexandria’s first and most influential citizens. When Alexandria was little more than a few temporary structures, he had towed a clapboard house up the Potomac and driven it into the riverbank. From the town's first freestanding home, he could keep an eye on his trading ships in port.11

Ann was described as “retiring” and “gentle,” a woman of means who had given up her right to “property and identity” upon her marriage to Ramsay.12 But while her son Dennis was fighting the British in the Virginia Continental Line, Ann set about to support the revolutionary troops from the home front.13

McCarty took advantage of her unusual social position: ordinarily, women of her status were not allowed to work outside the home, but her husband’s shop was on the first floor of their house. As such, she was permitted to tend the store.

When friends and neighbors stopped in to make a purchase, McCarty would ask if they would make an additional donation for the Continental Army—to round up their pence or Continental dollars to help “keep… the troops in boots.”14

Exactly what pitch McCarty made, or how she delivered it, has been lost to history. But she must have been good at it. Over the course of the war, she raised more money than any other individual female fundraiser in America. The most-cited amount is around $75,000 in 18th-century money, or more than a million dollars today.15 To facilitate her work, Fairfax County appointed her the treasurer of the County and of the City of Alexandria. At the time, it was almost unheard-of for a woman to hold such a post.

In the summer of 1780, General Edward Stevens received a list of financial contributions from women for the war effort. Ann McCarty Ramsay’s collection of donations included a set of watch chains, diamond jewelry, and rings, as well as a hefty sum of money. She donated “one halfjoe, three guineas, three pistareens, one bit. Do. for do. paper money, bundle No. 1, twenty thousand dollars, No. 2, twenty-seven thousand dollars, No. 3, fifteen thousand dollars, No. 4, thirteen thousand five hundred and eighteen dollars and one third."16

The enormity of this work and its value to the Continental Army did not go unnoticed. Thomas Jefferson purportedly wrote of McCarty’s efforts: “the amount collected was large and greatly to her credit, and let us give her all due honor for that work...”17

She maintained a lifelong friendship with George Washington, who congratulated her on her efforts after the war and attended her funeral in 1875.18 Today, Ann McCarty’s reconstructed clapboard home contains the Alexandria Visitors Center. The Alexandria-Washington Masonic Lodge is named after her, as is the local chapter of the Children of the Revolution.19

Digges and McCarty were only two of the many patriotic female citizens of the budding nation that committed their time, talent, energy, and resources to support the Continental Army. In the reshuffling of American civic and social life caused by the war, they stepped boldly out into the public sphere which had until then been prohibited to them.

Commenting on these new opportunities in Sentiments of an American Woman, Esther Reed cited examples from Biblical, Classical, and contemporary history where women had exercised political, social, and civic power to help their nations and societies. She wrote: “I glory in all that which my sex has done great and commendable… all those acts of courage, of constancy and patriotism, which history has transmitted to us.”20

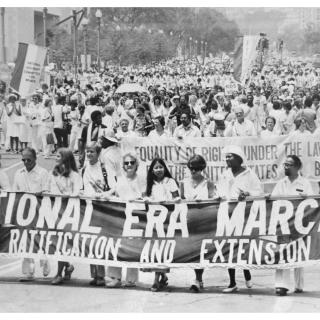

Many women answered her call in the 1770s, including Mary Digges and Ann McCarty. And since then, women from D.C. have continued to participate down through the decades in that honorable tradition of courage, constancy, and patriotism.

Footnotes

- 1

Sutherland, Riley. Virginia Women during the American Revolution. (2025, March 18). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-women-during-the-american-revolution.

- 2

Sutherland, Riley. Virginia Women during the American Revolution. (2025, March 18). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-women-during-the-american-revolution.

- 3

Maryland State Archives. “Mary Digges Lee.” Maryland Women’s Hall of Fame. Accessed October 29, 2025. https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/educ/exhibits/womenshallfame/html/mlee.html.

- 4

Maryland State Archives. “Mary Digges Lee, MSA SC 3520-2229.” Archives of Maryland, 1996. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002200/002229/html/2229extbio.html.

- 5

Maryland State Archives. “Mary Digges Lee, MSA SC 3520-2229.” Archives of Maryland, 1996. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002200/002229/html/2229extbio.html.

- 6

Mary Digges Lee to George Washington, 27 September 1780. Founders Online from NARA. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-28-02-0206

- 7

Maryland State Archives. “Mary Digges Lee, MSA SC 3520-2229.” Archives of Maryland, 1996. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002200/002229/html/2229extbio.html.

- 8

Mary Digges Lee to George Washington, 27 September 1780. Founders Online from NARA. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-28-02-0206

- 9

Mary Digges Lee to George Washington, 27 September 1780. Founders Online from NARA. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-28-02-0206

- 10

Maryland State Archives. “Mary Digges Lee, MSA SC 3520-2229.” Archives of Maryland, 1996. https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/002200/002229/html/2229extbio.html.

- 11

Converse, Gayle. “Alexandria Women’s History Walk.” Alexandria Celebrates Women, 2025. https://alexandriacelebrateswomen.com/alx-womens-history-walk.

- 12

Moore, Gay Montague. Seaport in Virginia. George Washington’s Alexandria: Exploring Alexandria’s Maritime Legacy. Good Press, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30747/30747-h/30747-h.htm#Page_55

- 13

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “Pallbearers at George Washington’s Funeral.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed October 29, 2025. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/pallbearers.

- 14

Converse, Gayle, and Pat Miller. “Women Have Been Essential Workers since Alexandria’s Beginning.” Alexandria Times, January 21, 2021. https://alextimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/01_21_2021-Alex_Times_WEB.pdf.

- 15

Converse, Gayle. “Alexandria Women’s History Walk.” Alexandria Celebrates Women, 2025. https://alexandriacelebrateswomen.com/alx-womens-history-walk.

- 16

Moore, Gay Montague. A halfjoe was worth 3,200 Portuguese reis, and a pistareen two Spanish reales.

- 17

Wikitree Editors. “William Ramsay (1716 - 1785).” Wikitree. Accessed October 29, 2025. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Ramsay-2904.

- 18

George Washington. Diary entry, 4 April 1785. Founders Online via NARA. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-04-02-0002-0004-0004 See footnote.

- 19

Robey, Donal. “Alexandria Lodge No. 39: Alexandria, Virginia 1783-1788.” Washington-Alexandria Lodge 22, 1999. https://aw22.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lodge39.pdf

- 20

An American Woman (Esther Reed), Sentiments of an American Women (1780). https://www-personal.umd.umich.edu/~ppennock/doc-Sentiments%20of%20An%20American%20Woman.htm

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)