The Buchanan Statue Debate: A Memorial Fifteen Years in the Making

Today, discussion regarding public monuments and which historical figures deserve to be memorialized is source of a heated debate among historians and the general public alike. But even a hundred years ago, D.C. lawmakers spent nearly fifteen years bickering over whether a certain someone’s likeness should or should not be set in stone.

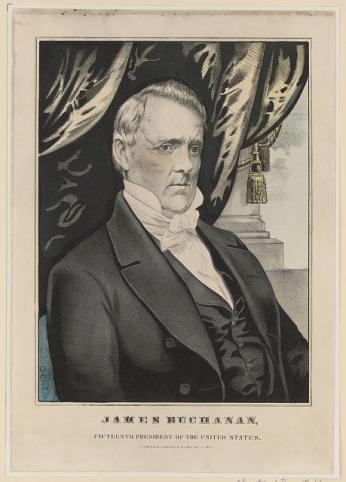

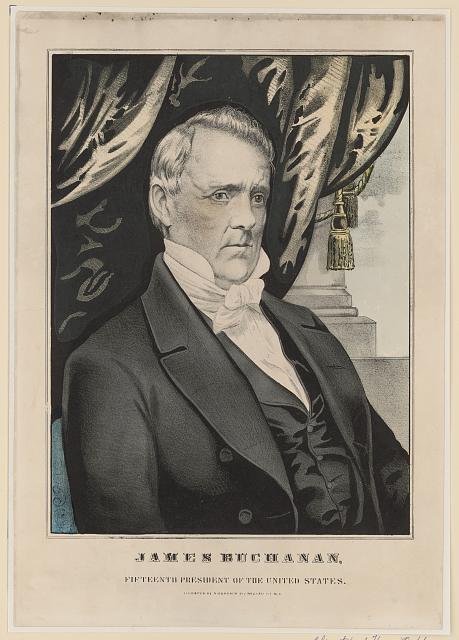

Who was the controversial figure? None other than James Buchanan, who served as U.S. President from 1857 to 1861. In the early 1900s, many believed Buchanan was “one of [the country’s] weakest presidents,” and it took Congress years upon years to decide whether or not Buchanan deserved public recognition.[1]

But whatever his political legacy, Buchanan had one thing that more glamorous figures like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison didn’t: money. A lot of money. $120,000, to be exact. To clarify, this was a fund that had been put aside solely for the purpose of constructing a James Buchanan memorial. Although it’d be funny to think Buchanan had a big enough ego to build a statue of himself, that wasn’t actually the case. It was Buchanan’s niece, Harriet Lane, who took it upon herself to cement her uncle’s legacy.

Lane had a close relationship with Buchanan throughout his life and presidency. After her parents passed away when she was quite young, Lane requested that “her favorite uncle” serve as her guardian.[2] Lane charmed nearly all who met her; even Queen Victoria sang her praises.[2] Since Buchanan was a bachelor, it was Lane who led Buchanan’s household affairs throughout his presidency.[2] Some claim that it was Lane who first garnered the title “First Lady.”

When Lane died in 1903, her will dedicated $100,000 in request of a public statue to honor her uncle. She was smart enough, though, to set an expiration date on the funds in order to amp up the pressure on the monument’s construction. According to the will, if Congress didn’t greenlight the statue in 15 years, or by July 2, 1918, the money would revert back to Lane’s estate. 15 years should have been ample time, right? Well…

In January 1916, only two years before the deadline, the question of building a “memorial of President James Buchanan” was still only being “contemplated.”[3] But while Congress took its sweet time drafting a bill for the memorial, the fine arts commission completed the statue’s design and thought of its potential placement. In October 1916, The Evening Star announced that “A Memorial to James Buchanan [was] To Be Erected in Meridian Hill Park”[4] and even published an illustration of the design. The Star explained that the money Harriet Lane had laid aside, which at this point had grown to $120,000 after interest, was enough to construct a grand bronze figure.[4] All of this, though, could only be promised if “Congress [gave] its sanction.”[4]

By the time December 1917 rolled around, though, Congress still had yet to decide on the proposed bill. The Evening Star wrote that D.C. “MAY LOSE BUCHANAN STATUE.”[5] The time limit for the funds narrowed with each passing day, and some in Congress began to worry. As The Star reported:

Unless prompt action is taken after the holiday recess, the National Capital will lose the hundred-thousand-dollar statue of President Buchanan…For fifteen years efforts have failed to secure a location for the statue from the House and the Senate, but Chairman Slayden of the House library committee, which is handling the Buchanan resolution, is going to try to get the question up for a vote soon after Congress reassembles next week.[5]

In true Congress fashion, “next week” actually ended up being five months later. The next mention of the Buchanan memorial in any newspaper is June 1917, when The Evening Star noted that Representative Linthicum of Maryland at last “asked unanimous consent to consider the resolution authorizing the erection of the statue to James Buchanan.”[6] Yes! Progress! Just kidding. Congress denied his request.

By the time the bill finally made its way to the House floor, it was February 1918. And even then, the process of passing the bill was far from smooth. The House debated over who “deserves to be commemorated” for nearly three hours.[7] Opposers argued that Buchanan’s sympathy toward slavery and state secession made him one of the nation’s most problematic leaders.

Representatives from all different states spit-fired “Attacks on Buchanan,” remarking that Buchanan had “indirectly sought to destroy the country;” that “comparison to Lincoln ‘bordered on blasphemy;’” and that Buchanan “deserved no remembrance from his countrymen.”[7]

The most dramatic blow came from “Representative Lenroot of Wisconsin,” who “declared that to accord the honor sought for Buchanan ‘recalled the almost traitorous action of a President. The best thing we can do for Mr. Buchanan is to forget him.’”[8] Former Speaker Cannon, however, advocated for the monument, pointing out that Buchanan was, “after all, President of the United States.”[8] Needless to say, “No vote was reached,” and Republican opposition to the statue provoked Democrats to object that “a political fight was being made.”[8]

It does seem that Republicans put up quite a fight, as their filibustering delayed the vote until February 21 when “Representative Madden of Illinois…insisted on a reading of the engrossed bill.”[9] By a vote of 217 to 142, the House finally agreed to erect a memorial. This was only the first step, though. The Senate had until July to agree to the measure before the funding disappeared, and they cut it incredibly close.

It was June of 1918 when “a row” over the Buchanan statue “broke out” in the Senate.[10] According to The Washington Post, Senator Smith of Maryland brought up the resolution, which sparked a “storm” of opposition. Senator Lodge of Massachusetts was the statue’s most vehement objector. Lodge dismissed Buchanan as “weak, timid, stubborn, indecisive, vacillating, and disloyal, adhering to neither one cause nor the other in the crisis of…the Civil War.”[10] Senator Lodge argued:

This joint resolution proposes at this moment, in the midst of this war, to erect a statue to the only President upon whom rests the shadow of disloyalty in the great office to which he was elected.[11]

President Buchanan was one of our weakest presidents; that no one can deny. To set up a statue of Buchanan, in the capital, where there is no statue of the elder Adams, who signed the Declaration of Independence, or of Thomas Jefferson or Alexander Hamilton or James Madison or James Monroe or the youngest Adams, to me would appear to be a reflection upon these really great men.[1]

Senator Smith, however, urged the Senate to pass the resolution, remarking that “for Congress to refuse to accept a statue of a former President of the United States was a reflection upon the country’s form of government."[1] Smith acknowledged Buchanan’s belief in slavery and states’ rights but also argued that Buchanan only reflected views common to his time. “It seems paltry,” said Senator Smith, “when our boys are in France today, to raise these long dead controversies. Slavery and secession are both dead. Why not let the painful memories of those days sleep?”[1]

In the end, Smith’s argument prevailed, and the Senate approved the memorial in a 51 to 11 vote.[12]

It’s impossible to say whether Harriet Lane predicted what a dramatic dispute her request would spark; but in what would have been a comfort to her, the Buchanan controversy seemed to die down with time. It took another 15 years for the city to complete the bronze monument. By then, it appears the more negative aspects of Buchanan’s legacy were forgotten; or perhaps there were simply more pressing matters to worry about. Either way, President Hoover sang Buchanan’s praises at the unveiling ceremony:

James Buchanan, whom we honor here today, occupied the presidency at a moment when no human power could have stayed the inexorable advance of a great national conflict…Mr. Buchanan served his country during a long and active life…His career was rich in achievements and gratitude of his country.[13]

Today, the monument sits nestled in the southeast corner of Meridian Hill Park, just between the neighborhoods of Columbia Heights and Adams Morgan. The statue’s inscription reads: “President James Buchanan, the incorruptible statesman whose walk upon the mountain ranges of the law.’”[14] Though the bronze has turned green with time, Buchanan still looms grandly over the park. One would never guess just what a journey it took for him to get there.

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d June 15, 1918, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 9

- a, b Mark Roth, “The first first lady: Buchanan's niece enlivened social scene,” Pittsburgh Post Gazette, https://www.post-gazette.com/life/lifestyle/2006/12/05/The-first-first-…

- ^ January 1, 1916, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 12

- a, b, c October 12, 1916 , Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 11

- a, b December 29, 1917, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 9

- ^ June 20, 1917, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 9

- a, b ATTACKS ON BUCHANAN: "TRAITOROUS," ASSERTS LENROOT: ASKS HOUSE TO ... The Washington Post (1877-1922); Feb 14, 1918; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 9

- a, b, c February 14, 1918, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 9

- ^ February 21, 1918, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 7

- a, b BUCHANAN STATUE SITE AUTHORIZED: VOTED BY SENATE 51 TO 11; A DISLOYAL PRESIDENT, SAYS LODGE. The Washington Post (1877-1922); Jun 18, 1918; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 7

- ^ BUCHANAN STATUE ROW IS RENEWED: LODGE, IN SENATE, SAYS FORMER PRESIDENT WAS "DISLOYAL." The Washington Post (1877-1922); Jun 15, 1918; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 4

- ^ BUCHANAN STATUE SITE AUTHORIZED: VOTED BY SENATE 51 TO 11; A DISLOYAL PRESIDENT, SAYS LODGE. The Washington Post (1877-1922); Jun 18, 1918; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 7

- ^ June 26, 1930, Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.), Washington (DC), District of Columbia, Page 2

- ^ BUCHANAN STATUE VICTORY IN HOUSE: By 217 to 142 Members Vote to Place It in Meridian Park. The Washington Post (1877-1922); Feb 21, 1918; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post pg. 2

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)